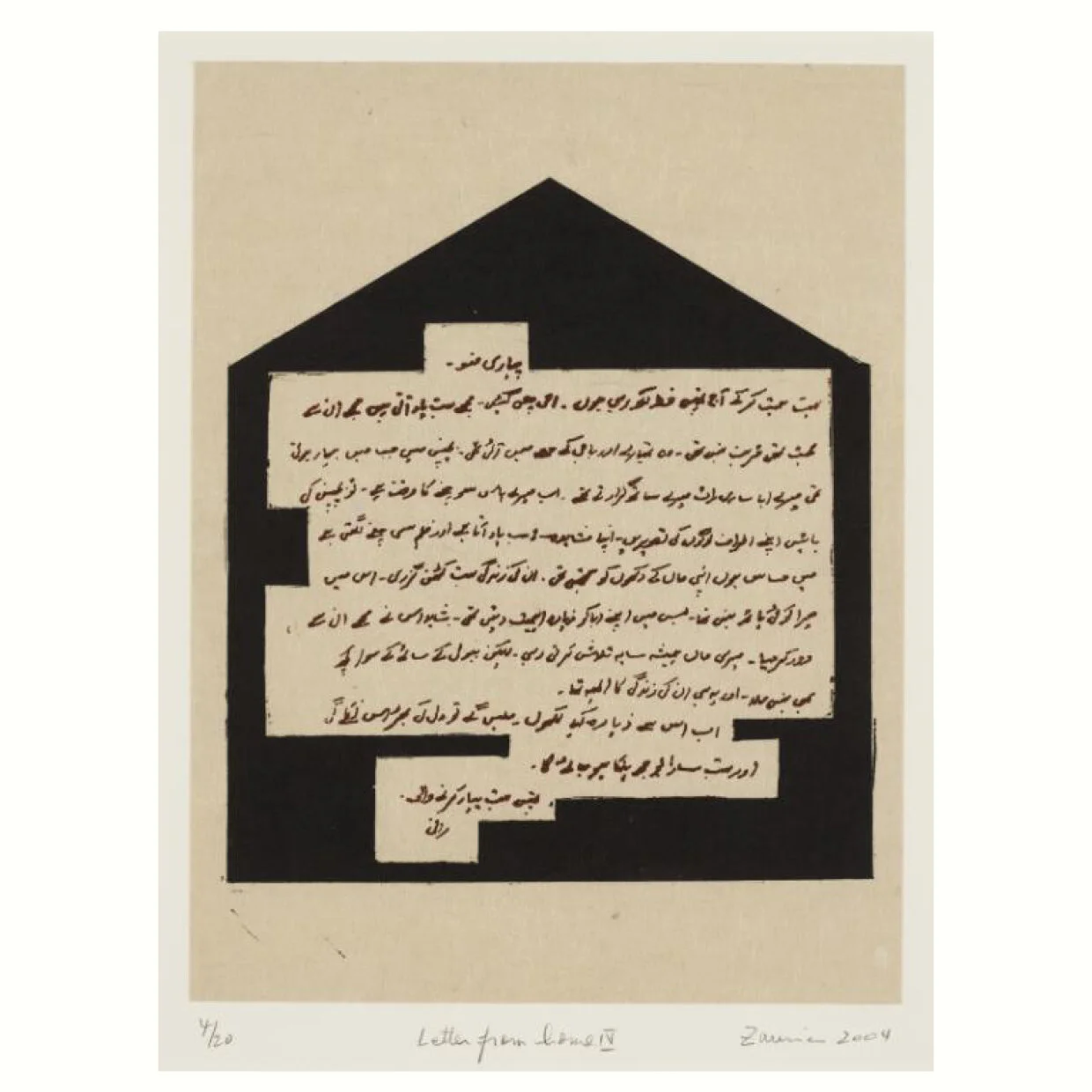

Image: Zarina Hashmi

remembering her grandmother’s apartment as a museum of objects Knitted with nostalgia, isha solanki reimagines home as an everchanging archival space for story-telling & transcendence

words Isha Solanki

The sky is all lilacs and pinks, it is a quiet, dusky evening. ‘I don’t see many sparrows’, my grandmother says, ‘do you think they’ve gone away?’ A question that often surfaced as the evening sun cast shadows in the living room of her small apartment.

My grandmother, a fragile woman with a stubborn wit, lived by herself for the latter half of her life. A quaint flat with large windows for a balcony, she moulded the bricks into a place of safety and comfort.

To accessorise, just like any other, she kept a distinct collection of odds and ends in the house. As a child, I could always find stuffed animals to play with there. Be it handy fridge magnets or play-size cuddle bears, Nani (my nickname for my grandmother) always managed to amuse one with a fuzzy animal friend. Her collection of inanimate objects could be extended to the modest temple in her bedroom corner with a selection of gods to implore upon. Perhaps she had a fascination with garnering figurines.

Rummaging through the mundane objects of her household, I am reminded of the vastness of her small apartment and the little corners she sculpted out for herself. It was only after her passing that I grasped how little space she occupied and yet her absence is so colossal.

“However ordinary, this house holds a woman’s history by bearing the objects of her being.”

Losing its dweller to death, the apartment now stands with its walls eloquently holding all that meant the world to a frail woman, memories she hoarded in the shape of diaries, greeting cards and photographs. She habitually tucked these under the sofa cushions to avoid creases, a method of preserving those memorabilia she held close to her heart.

Amongst these is a bundle of letters received and some written never to be posted. A canvas basket full of areca nuts and a brass nut cutter with a row of bells on its upper end - her most prized possession. The ease with which she used the sarota[1] to meticulously chop her supari[2] in thin, even slices always stirred wonder in me. How delicately she plunged the blade against the tough brown exterior when it could have easily been pink flesh.

The essence of the objects in the house impels me to move further from the insignificance of hoarding. The space metamorphoses into an evocative of everyday, telling the more individualistic and trifling tales of she who was. Leaving behind a trail of ordinary yet mysterious chattels, I chart new memories through old stories of her belongings.

However ordinary, this house holds a woman’s history by bearing the objects of her being. It stands as a fort, allowing one to imagine an alternative narrative of her life; the refuge she sought from the afternoon sun splinters and the window that eavesdropped on the neighbour’s babble—it is now the home of her leftover pleasures.

Isha’s grandmother’s home.

Revisiting this house has revealed what one might call ‘the margins’ of her being. Nani had her own solo acts of keeping busy in the larger scheme of living. These involved spending hours rubbing sandalwood on a grindstone to extract chandan[3], which she would later use to adorn the foreheads of her copper-coloured deities. Knitting had always been one of her strongest suits. I distinctly remember her watching the television, sitting on the couch against the window, whilst her fingers effortlessly knitted a jumper in a peachy orange yarn. The dexterity of her nimble hands at her age of seventy-two astounded me. Perhaps this is what they call ‘muscle memory’.

I grew up knowing her as the old wise woman who had stories tied at the dangling end of her saree and who would often produce them during the post-dinner banter; all the matriarchs would sit up and talk of inflating prices of wheat, how the tea that evening almost burnt their tongues on the first sip but by the time they got to the second sip, a fat layer of cream floated atop and the tea discoloured to an unpleasant tinge.

They had all spoken of desire and despair amidst these conversations. Often discarded as ‘gossip’, these little communions of my aunts, sisters and mothers, were a space of solace to unburden domesticity and articulate loss in a language of fortitude and forbearance. As a child, I celebrated these gatherings and being around women who shared laughter and warmth not only on account of having similar hazel eyes but because they understood the anxiety of the future, wielded endurance for each other and taught me to persevere.

I have been reintroduced to my grandmother and the solitary ways in which she existed by re-addressing her home. This apartment then reconstructs itself as a personal museum still embracing the naphthalene and nostalgia of a life lived in it. My grandmother’s memories are resettled in her belongings such that I can reimagine her history through these. These objects form their own landscapes of a larger chronicle moulded by those who knew her. The apartment not only stands witness to her life but also penetrates my memories of a home, leading the way to return, to hold on to a home that archives gestures.

Isha’s grandmother, Urmila.

Growing up, we are often taught that foraging through another’s effects is inappropriate. But shuffling through her drawers, I sight no wrong. Instead, there I am overcome with a sense of repose in discovering a drawer full of knitting needles. Absurd as it may sound, the stack of long grey needles with numbered tips, found tied together by a weary elastic band, reminds me of her quiet ways of occupying the day, of how she gently weaved her concerns in colourful woollen twines, sharing her warmth.

Fabrics play out a romance with the skin when a sense of touch incites certain memories. Printed in sombre floral patterns on muted shades, this attire that she carried with such flair buried her bony structure. Her vanity crinkled in these nine yards of linen. The occasional turmeric stains gave her the persona of a worldly woman, outliving her years with every dawn. Until one day when her lungs could only hold the incense fumes, not air. In my imagination, she does not exist in an ensemble other than her staple sarees. Her almirah was a portal to another world. Not merely a closet but a safe-keeper of soft cotton sarees with potpourri tucked between its pleats, reminiscent of the tender ways in which she continues to be.

“It has been possible to grieve her absence through the presence of these remaining objects and their imagined stories.”

The tactility of belongings refers to a co-existence of home and memories such that one is required to construct the other. It is the home that accommodates these memories that stir up a sentiment of nostalgia, letting me have brief flirtations with a time in the past. A languid silence that now stands still in the air of this apartment replaces the redolent talcum powders that she often wore.

It has been possible to grieve her absence through the presence of these remaining objects and their imagined stories. By coherently piecing it all together, I resort to remembrance for repose. The tangibility of these mundane objects has opened up dialogues around home, enabling me to understand it in its physicality. I have realised that these walls, that once confined Nani in nuptial responsibilities, have also contained and held her.

In living by herself for the better half of her life, she was able to reinvent this space without a livelihood. Now while I write about her, trying to recall her quirks and producing stories, mostly fabricated with memory, perhaps the image that flashes here is how I have always thought of her or at least longed to. By creating fictions in empty spaces of her timeline, I am reminded of how fallible memory is. It is not to falsify but to construct narratives in those rifts of her life that I was unaccustomed to. In leaving me with the miscellaneous of her life, Nani taught me to think through memory.

Notes

1. Sarota: A nutcracker used for Areca nuts

2. Supari: Hindi word for Areca nuts

3. Chandan: Sandalwood paste

Isha Solanki is an Indian writer and editor with a background in the cultural and creative industries.