Image: Katie Dorame

Pomo woman Stormy Ogden reflects on her experience in America’s criminal justice system & considers the criminalisation of Indigenous women

words Stormy Ogden

Trigger warning: Sexual abuse

The following is an excerpt from Neo-Colonial Injustice and the Mass Imprisonment of Indigenous Women, a text exploring the sharp rise in Indigenous women imprisonment (Indigenous women are the fastest-growing segment of the prison population in Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and North America) from the perspectives of academics in criminology, sociology, Indigenous and gender studies and from those embedded in Indigenous communities. This piece, written by ex-offender Stormy Ogden, examines the systemic criminalisation of American Indian women and considers the impact such trends have on Indigenous identity. Stormy reflects upon her experience and activism both within and beyond the United States’ criminal justice system in an attempt to remove shame from incarceration, reclaim her native identity and condemn the country’s historical and continued mistreatment of American Indian women.

Resistance

The reservations, the boarding schools and the mission system set the path for the life of a Native Indian long before I entered the state prison to start doing those five years. My DNA, my ancestral blood knew of the fear, the humiliation and the pain of being a human locked away mentally, emotionally and physically. As Native people of this Turtle Island, we come from a history of being incarcerated and having our identity, language, culture and religious ceremonies “beaten” out of us. But it is from that same ancestral blood, that blood memory, that also knows about resistance. Without those acts of resistance, I would not be here to share my stories with you.

I became involved with prisoner rights organisations and began to be invited to speak out and write of my experiences of being an American Indian woman in prison. I came to realise that the description by Angela Y. Davis of the prison industrial complex (PIC) “as a complex web of racism, social control, and profit” (Davis, 2001, p. 59) had its beginnings in the genocidal progress of manifest destiny; and for the natives of California this “blueprint” was achieved originally through the Spanish missions of Alta California. Lightfoot clearly lays out the similarities: “The Missions resembled penal institutions in many respects, with the practice of locking up some neophytes at night [...] the use of corporal punishment, and the relatively tight control of behaviour” (Lightfoot, 2006, p. 62).

It was with this new awareness that in 2005 at the Hoopa Wellness Conference on the Hoopa Indian Reservation, I first presented a workshop entitled From Mission to Maximum Security: The Prison Industrial Complex in Indigenous California. And, to this day, I continue to look at the PIC through the eyes of a Californian Indian woman and ex-prisoner of the California Department of Corrections.

“the more I read about the courage and survival of this Tongva woman, the more I wondered why this part of our history was never taught”

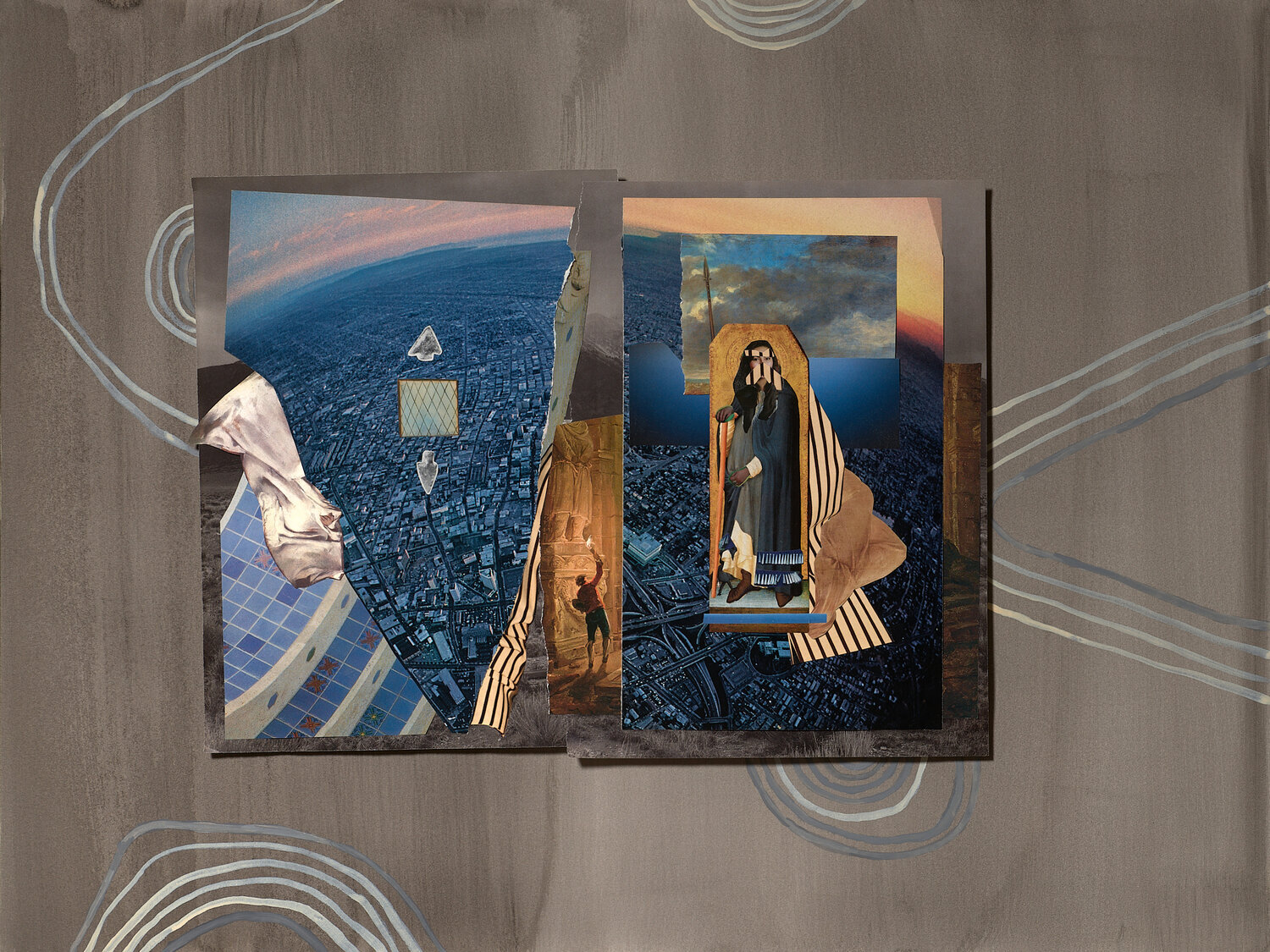

As I was searching for examples of resistance in early California, Dr. Kimberly Robertson (Mvskoke) suggested to look into Toypurina, a medicine woman of the Tongva Nation—a nation later to be known as Gabrielino because of their association with the Mission San Gabriel just east of what is now known as Los Angeles. The more I read about the courage and survival of this Tongva woman, the more I wondered why this part of our history was never taught and, if it had been, then maybe I would not have been bullied at recess for “eating bugs”.

The peoples of Toypurina tribe had rejected joining the mission and being baptised, although this did not stop them from knowing what the conditions were for the mission’s baptised neophyte [1]. It was in 1785 that Nicolas José, a tribal member and neophyte, sought help from Toypurina. Being well known as a respected medicine woman, it was thought she would be instrumental in the recruiting of other villages to join in the revolt against the friars and military officials inside the mission. Ordered by Governor Fagess, the baptised Indians were prohibited from performing seasonal dances; his reasoning behind this was, “by prohibiting such dances, the Indians would eventually forget them and assimilate faster into the Spanish life of Alta California” (Castillo, 2015, p. 165). It was in the fall that they held their annual mourning ceremony, a time during which death rituals were performed to release the soul of the deceased from the earth so they could go to the land of the dead. They believed that not performing these dances would endanger the spirits of their living relatives. The soldiers stationed at the Mission were told about the plot and stopped the riot, capturing Toypurina, and other leaders involved. Awaiting trial, she was held for 16 months in solitary confinement before being banished from her home to the mission Carlos Borromeo. In the end, she was forced into being baptised and her name was changed to Regina Josefa Toypurnia.

Image: Toypurina and the San Gabriel Mission Revolt

Toypurina’s legacy of resistance to oppression and her protest against Spanish colonialism will not be overlooked or forgotten. Her story lives on in the play Toypurina (San Gabriel Mission Playhouse, 2019), which was performed in 2014. There is a new revolt on the Tongva lands, which is meant to educate people about the slavery and genocide that happened on the stolen land on which they stand.

A New Revolt: #JailBedDrop

In early 2017, I was introduced to Kimberly Robertson and Jenell Navarro (Cherokee descent) who are co-creators of The Green Corn Collective (GCC). They had joined together with other local Los Angeles artists who came together to be part of the JusticeLA #JailBedDrop campaign (JusticeLA, 2019). This action was meant to bring awareness and dialogue around the County’s decision to expand its jail system with $3.5 billion in funding. The GCC—“a constellation of Indigenous Feminist Bosses” (Anderson, Campbell & Belcourt, 2018, p. 337)— created their Indigenous feminist #JailBed, wanting to bring attention to the high rate of native people incarcerated in US prisons. On Christmas Eve, they placed their decorated bunk bed at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Downtown Los Angeles (Pratt, 2018).

The reason behind this location was to bring attention to the fact that up into the 1850s Indian people were sold as slaves on Temple Street.

I highly suggest going to their website to see the beauty, the healing, and the Indianness that was woven into the many different offerings on each bed of the bunk. Also included were several printed zines that could be taken to read, which highlighted the issues around mass incarceration since 1492. I asked Kimberly and Janell to tell me the meaning of their name, and how and when they got together:

The collective was founded by south-eastern native feminists and our largest ceremonial and festive time of the year is held before the corn is harvested. This ceremony is called the green corn ceremony and it elevates new beginnings and a time of renewal [...] from over a decade of collaborative Native feminist dialogues and projects. However, it formally began in 2017 and the JailBed project was one of the first projects carried out by the collective (pers. comm., 7 July 2019).

My experiences resonate strongly with those of too many other Native women. I had spent years finding ways to fight against all the emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and the methods I found were in alcohol, drugs, sex and physical abuse against myself and others. The self-abuse stopped when I entered prison but not the abuse by others; this time it was at the hands of the prison administration. Looking at my experiences in prison, I can clearly see the connection between the missions, the boarding schools and what we go through in prison. On the first day when we first get off the bus, we are no longer our own person; we belong to the state of California, and we become cheap labour for their profit-making machines. We are stripped of our identity; names are replaced by numbers, and for us, the pride of being native is stripped down to being Other. Then street clothes are taken and replaced with a state-issued uniform; then on to the showers and being de-loused [2]. And one last thing before they are done—the search for contraband that, in some facilities, came with a cavity search, which is, at any time, humiliation. During my time there were not a lot of women COs. The male guard would stand outside the room, but still, it felt like I was sexually abused. Again.

Across all the prisons, Native prisoners have that one common struggle, which is the right to pray in the Indian way. Native men are still fighting to wear their hair long, although I recently read about a huge victory for some Native inmates in Texas who won their lawsuit to be allowed to wear their hair long (Blakinger, 2019).

With each Native person we lose to incarceration, we lose important human and cultural resources in their tribes and families. I lost most of my 20s to being locked up. In cases where there are children in the family, they are affected by the loss of their family member and the loss of their childhood.

“With each Native person we lose to incarceration, we lose important human and cultural resources in their tribes and families.”

Conclusion

I choose to end my chapter with this poem by an amazing Menominee, two-spirited woman and all-around badass. I met her years ago at the first INCITE conference in Santa Cruz. We have been friends ever since. Chrystos carries with her years of wisdom as a self-educated artist and writer, and is an activist for several Native rights and prisoners’ causes. She wrote this poem when she was allowed into the Women’s Federal Prison in Dublin, California. Chrystos was bringing in her healing through the words, through her voice, to the Indian women of Four Winds:

Going into the Prison

The guard growls, What’s this?!

Poetry, I answer, just Poetry

He waves me through

With a yawn

That delights me

So, I smuggle my words in

To the women

Who bite them chewing starving

I’m honored to serve them

Bring color music feelings

Into that soul death

Smiling as I weep

For Poetry who has such a bad reputation

She’s boring, unnecessary, incomprehensible

Obscure, effete

The perfect weapon

For this sneaky old war-horse

To make a rich repast of revolution

Notes:

1. Good time was credit that was given to each prisoner as a sentence reduction who maintained good behaviour while imprisoned. Prisoners are eligible for this if they are serving a prison term more than one year.

2. This happened to me each time I went to Juvenile Hall.

References

Chrystos. (1995) Fire Power. Vancouver, BC: Press Gang Publishers.

Stormy Ogden is a tribal citizen of the Kashia Pomo and direct descendent of the Tule River Yokuts. She is a community organiser and speaker who helps to send Native language material and other resources into prisons for Native women and men.