Image: BrownCoffeeMoka

The writer and researcher considers Black mental health and why we need to be conscious of cultural contexts when treating mental disorders

words Elvira Vedelago

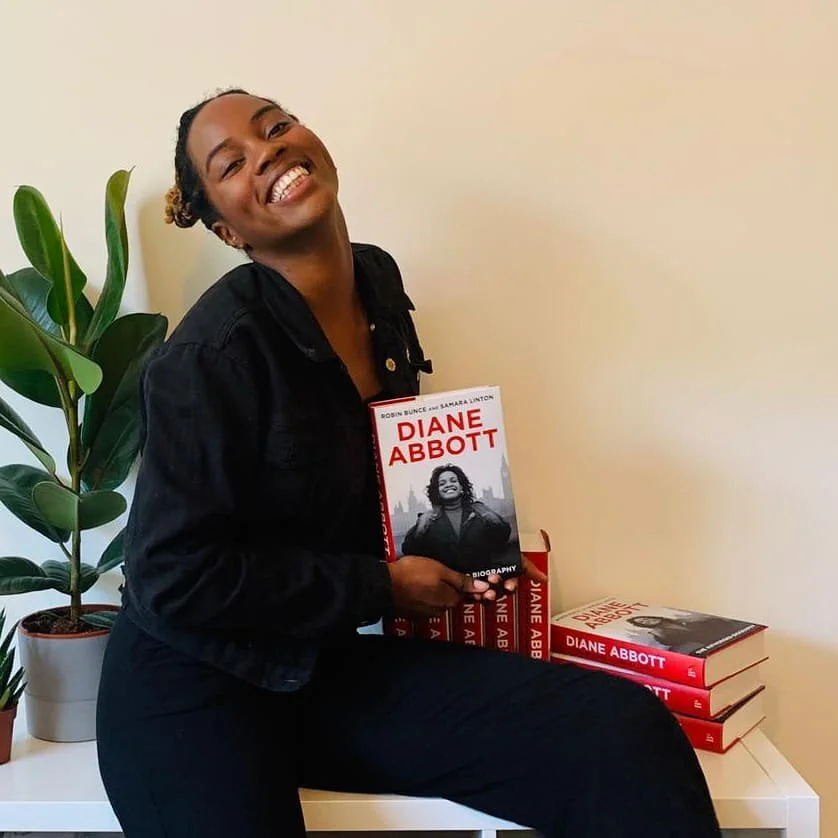

From her home in South London, Samara Linton shares a story about US Congresswoman Terri Sewell, the first Black woman to serve in the Alabama Congressional delegation and a long-time friend of British MP Diane Abbott. While researching Black women in politics, Terri was surprised to see how far behind the UK was in recognising Black people in political spaces and to learn that America had managed to place Black women in high positions of office before Britain - a nation which often prides itself on being more ‘tolerant’. “We don’t like to talk about race and identity in the UK and I think it’s a disadvantage to Black women in particular,” Samara notes on a Zoom call a few weeks after the release of Diane Abbott’s The Authorised Biography, which she co-edited with Robin Bunce. Recording Black British women’s experiences is of particular importance to Samara and she credits her passion for sharing the untold stories of those people often ignored and pushed aside by society as a motivating factor behind her career switch from medicine to media. An award-winning writer and researcher, Samara’s work focuses primarily on health, race and gender; in 2016, she co-edited an influential report on Ebola affected communities for the Africa All-Party Parliamentary Group and two years later, she co-edited The Colour of Madness, a seminal anthology exploring Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic mental health. In conversation with POSTSCRIPT’s Features Director, Samara reflects on her own journey managing mental illness as a Black British woman and addresses the political landscape of mental health in the UK.

ELVIRA VEDELAGO: I came across an old crowdfunding video for The Colour of Madness online where you mentioned wanting to become a psychiatrist. Did your experience in the mental health field impact your decision to leave medicine in any way?

SAMARA LINTON: When we started The Colour of Madness, I was in my final year of medical school and by the time we were finished I was working as a doctor. My first job as a junior doctor was on an acute psychiatric ward. It was a triage ward, so that means people came in from A&E or often police would bring people in. Because we were based in East London, often a lot of Black people were brought in by police. Newham is a very ethnically diverse area and we had a lot of Section 136s where people are brought in by police because they have been seen to be acting strangely in a public place. I loved working in mental health and exploring sides of the human mind. At the same time, working in psychiatry was very difficult for me, especially because of the relationship that it has with Black communities — the way in which it has been used historically and in many ways still mirrors the criminal justice system and other systems of control that Black people have been oppressed by. So while I enjoyed my interactions with patients and helping people when they are at their most vulnerable, it was difficult to do that within this greater system of psychiatry. It was also very triggering working on that ward as someone who has their own mental health difficulties. Even though I was supported by my seniors, it would be silly of me to say that it didn’t have some effect on my decision to leave medicine.

If you’re comfortable, could you tell me a bit about your personal experience with managing mental illness?

My mental health difficulties really kicked off when I was at university. I think it was the demands of studying medicine but also just general social stresses which we all go through when we go to university for the first time and we are away from home. The underlying issues were there years before, and now looking back into my teenage years I can see that, but the catalyst was that intense period at university. I was diagnosed with depression at that time. It took me a few years to settle into finding a medication that worked for me and finding a therapist that I felt I could have a relationship with. But then a couple of years ago, my mental health got quite bad and I was referred to secondary mental health services, so I was under a community mental health team for a few months. That overlapped with the time when I was working as a doctor, which was very difficult for me. I had to battle with my ego and pride because I was being treated by my colleagues. It was a local team and it was an area that I was living and working in, so I was seeing familiar faces even if I hadn’t worked with them before. It really challenged me to take seriously how much I believe in the fact that mental health difficulties aren’t something to be ashamed of. I’ve always preached that but at the time it felt like a personal failure. And while I’m managing my mental health better, I can’t say I’ve recovered and I am completely neurotypical now.

“working in psychiatry was very difficult for me, especially because of the relationship that it has with Black communities - the way in which it has been used historically and in many ways still mirrors the criminal justice system and other systems of control that Black people have been oppressed by”

For anyone that doesn’t understand depression and anxiety, could you describe what your internal world is like?

Right now, which is a normal day, I can feel a sharp, burning pain in my arm. Sometimes I feel nauseous. It’s just this general feeling of unease that I carry in my body day-to-day and that unfortunately feels a part of who I am. When it gets really bad, my breathing starts to feel funny and I feel like there is not enough oxygen in the air. That’s what a lot of people describe as a panic attack. I haven’t ever struggled with anxious thoughts, my anxiety has always been very physical. Whereas, I describe my depression as walking around with a fog in my head. Everything feels a bit hazy and nothing feels very real. I don’t feel connected to my physical space or to the people around me. Other people might struggle with low moods and negative thoughts about themselves, whereas for me, it’s always felt like I’m disappearing inside myself and my connection to this world is being lost. The process of trying to be present is incredibly painful, so I want to do the opposite. My depression is more existential and my anxiety is very physical but obviously, I experience them together.

When you got your diagnosis, how did your family respond?

My mum was really scared when I told her that I was going to start antidepressants; she was terrified of the idea that taking this drug might change who I am. She, like so many other Black women, had heard countless stories of what happens to Black people when they engage in mental health services, the fear that they will lock you up, drug you and drain you of who you are. She supported my choice but it was really difficult until she saw that the medication was helping me and I was more myself than I had been before. Naturally, her fears are justified because for many people, when they enter mental health services, it can be the worst thing to have happened to them. There is variation in experience and I was in a unique and privileged position in that I came from the medical world and I understand the systems that are being used, so my experience would have been better than the average person’s. My dad was alright with medication but therapy made him freak out a bit. He felt that I should be able to talk about my feelings with the family. The reactions differed based on people’s preconceived ideas about the system but also where support should come from. Now, I talk and write about my mental health a lot so it’s not really a surprise anymore. Still, you have aunties who are like “why are you wasting money on therapy” but beyond that, I think people are more understanding than they were initially.

Editors of The Colour of Madness, Samara Linton (left) and Rianna Walcott (right). Image from Media Diversified

When talking and writing about mental health, are you seeing less stigma across the board?

One of the big shortcomings of the mental health narrative that we have - and the ways in which we focus on mental health stigma - is that it is very focused on depression and anxiety. The other more ‘unusual’ mental health conditions, we push to the side because we don’t want them to get in the way of the mental health message: we all have it and it’s completely normal. Because we’re trying to push this message of acceptance, we hide away the mental illnesses that are undesirable. So I don’t think the stigma for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorders has really changed in the last 10 years. Those conditions are alien to a lot of the public and there is more fear and distrust of them.

What else do you think is missing from the public conversation on mental health at present?

One of the most common slogans is ‘1 in 4 people have mental health difficulties’ and while I get why that is so popular and why it’s supposed to normalise the experience, it completely disregards that it’s not a random lottery draw as to who gets mental health difficulties and who doesn’t. There are certain things in this life that make you more vulnerable to mental health difficulties and those things are societal and those things are political.

Well said.

It makes me wary as well. People sometimes refer to me as the spokesperson for Black mental health but as a cis woman, my story is more acceptable to a lot of the public. It makes it comfortable for them and the reality is the situation isn’t comfortable. The fact is that certain people, because of the way they look, their sexuality, their gender, their immigration status, because of the way they move through this world, are more likely to have mental distress than others. The figures are disgusting because these are things that are completely in our control as a society. Because our mental health campaigns are meant to be cute and friendly, we don’t want to get political or controversial. But then whose interests are we really serving?

The fact is that certain people, because of the way they look, their sexuality, their gender, their immigration status, because of the way they move through this world, are more likely to have mental distress than others.

I completely agree. One of the things I feel like we don’t talk about enough when we look specifically at demographics is Black women’s mental health. For example:

Generally, black women have higher rates of mental health disorders than any other group in the UK. A study found that 29% of Black women had experienced a common mental disorder [and were] significantly the largest group, followed closely by mixed-race women.

Black women are more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder than any other demographic in the UK.

A study found that young black women were the demographic most at risk for self-harm across three UK cities.

This is big stuff and I’m shocked that as a society we don’t talk about this more. Why do you think we are seeing this disparity?

The reality is that as Black women we are walking through this world as Black and as women, and often with many other identities that make us vulnerable to the pressures of society. I remember when I first found out that Black women had such high rates of common mental health disorders, I was so shocked because for a long time I thought that I was unusual as a Black woman who was struggling in this way. I thought it was unusual because of the way in which we talk about Black women: they’re strong, resilient and magical, superhuman beings that can do everything. I found that the more I talked about it, especially talking to my elders - Black women from my parent’s generation - I realised that they probably would never go get a diagnosis or tell their GP they are struggling, but it becomes so much more obvious to you that Black women have been and continue to be suffering because of the interactions of patriarchy and racism. There are things that specifically we experience because we’re Black and women. It’s not just that they add together, there is an additional experience that comes about with these overlapping identities. So when I think about it, it’s not surprising at all. However, it’s encouraging to see many young researchers (usually young Black women) who are making it their work to research, record and document Black women’s experiences in the UK. Because it hasn’t really been done before. Even with Diane Abbott’s biography, why is this the first one that’s been written? It’s 2020, that’s shameful that it should take this long for this kind of story to be documented.

Image from @Samara_Linton

I often worry about the superwoman narrative. The reality is that ignoring or even lauding Black women’s management of suffering is really dangerous in respects to health and how these issues can manifest physically in our bodies. I once went to a talk from Dr Gabor Maté on the very serious physical implications associated with stress. He linked African American women’s increasing reports of asthma to the stress of experiencing racism. It seems obvious, yet looking at UK studies on racism and mental health, there is often a comparative narrative that suggests non-black people of colour don’t seem as negatively impacted by racism as Black people. I understand the nature of research to compare results for validity but I think that narrative undermines the experiences of Black communities. What do you feel is the specific difference in Black mental health?

It’s a question that people like to raise a lot. The first thing to say is that other communities do suffer from mental health problems. It’s important to recognise that and then recognise the differences. We know that different ethnic groups have different social standings. I know that the way that I’m perceived is not the way that my friend whose parents are from Bangladesh is perceived. And it’s not to say that the way that she is perceived is necessarily better. In some cases, it might be worse depending on what prejudices people hold. However, the stereotypes that surround our communities are very different and people are disingenuous when they try to pretend that all racism and discrimination is the same. Our communities face different economic stresses and statuses that have a massive impact on mental health. There are certain groups of ‘people of colour’ who are more accepted and who are better able to assimilate and integrate than others. There are groups in which assimilation is something that they pride themselves on. That will have an impact on the way that they are perceived and the discrimination that they face. Then also, if you do have mental health problems and you go into the mental health system, there are very few Black psychiatrists, while there are considerably more South Asian psychiatrists. So the chances of being treated by somebody who is from your background and who is better able to understand certain nuances of your experience is different among different ethnic groups as well.

“When you’re already feeling misunderstood and like you don’t belong in this space, to have to explain yourself and justify your experiences—which a lot of people have to do with their therapists—I think is very damaging.”

Let’s talk about cultural contexts and why you think there is a need to be particularly conscious of that within mental health?

It’s interesting because I used to think what mattered is that you were a good therapist and I still think that matters. What changed for me was that a few years ago, I received some free counselling through Mind (the mental health charity) and they assigned me a trainee psychologist who was a Black woman. In those sessions, certain things came out that had never come out before and I realised it’s because there were certain understandings between us that didn’t need to be explained. I didn’t have to explain to her why I had certain views about myself and I realised the ease of aspects of the conversation because of that shared understanding. That was the first time it really dawned on me that this mattered and that I needed more of this because so much of my mental health is tied to my Blackness and my womanhood. From then, I actively sought out Black, female therapists. It’s not just because a white therapist can’t understand my experience or won’t be able to relate to me. It’s just that I feel like I don’t have to explain myself as much. Especially when you’re paying for therapy - it’s expensive and you’re wasting time trying to explain basic concepts to someone and educating them about who you are before you can deal with those concepts. Unfortunately, it’s a privilege to not have to waste time doing that because it’s not something that people easily have access to unless you are a cis white, straight male/female. When you’re already feeling misunderstood and like you don’t belong in this space, to have to explain yourself and justify your experiences—which a lot of people have to do with their therapists—I think is very damaging. You can’t have a positive therapeutic relationship when you’re having to justify your experiences.

Okay, my final question. How are you reclaiming or establishing control over your own personal narrative when it comes to your mental health?

I’m just doing away with shame. If I say something about my mental health and people look a bit uncomfortable, it just doesn’t bother me in the way that it would have in the past. It’s so much more freeing. This shedding of shame means that even if things are stressful and I’ve got various other mental health struggles, shame isn’t one of them and shame isn’t a burden that I have to carry. That’s been really great.

This conversation was originally featured in The Reverie Issue.

Visit Samara’s website to learn more about her work.