Image: Ronan Mckenzie at HOME

photographer Ronan Mckenzie on ‘HOME’—her multifunctional creative space for Black and Indigenous creatives of colour—and its recontextualisation of the arts industry

words Shaelyn Stout

Set off a mildly busy North London high street, HOME by Ronan Mckenzie is a multifunctional creative space geared towards a recontextualisation of the arts industry and continued support for Black and Indigenous creatives of colour. One of the few Black-owned, artist-led art spaces in London, HOME blends artistic practice and theory with homely comforts to offer a unique, communal experience that redefines ‘home’ as a connection to and collaboration with one's own creative community. On paper, HOME is made up of two components: curated exhibitions and free-to-use studio space. In translation, visitors are offered inspiration and motivation from exhibited works as well as the opportunity to refine and develop their artistic practice in a safe, non-judgmental environment. These outcomes, paired with HOME’s focus on Black and Indigenous artists of colour, reflect an innovative art space that distances itself from the intimidating nature of the creative world while still combating racial and ethnic disparities found within it. In a conversation with POSTSCRIPT, Ronan Mckenzie—photographer, curator and Founder of HOME—discusses the value of and inspiration behind her project and its call for a fundamental reframing of the ‘art space’ as we know it.

At just 26-years-old, Ronan Mckenzie has more than ten years of experience learning and working in the arts industry. From an internship at i-D to her now thriving career in commercial and fashion photography, Ronan’s journey through the art world seems not only to have shown her how the industry must change but also that such change could be hers to make. In my pre-interview research of the artist I was intrigued to learn of her 2018 exhibition “I’m Home”—a precedent to HOME the space and, in many ways, an homage to the Black British female experience. It was becoming clear how Ronan’s North London roots and passion for diverse representation in creative spaces led to the birth of HOME. But what I really wanted to discover was why that name was so significant.

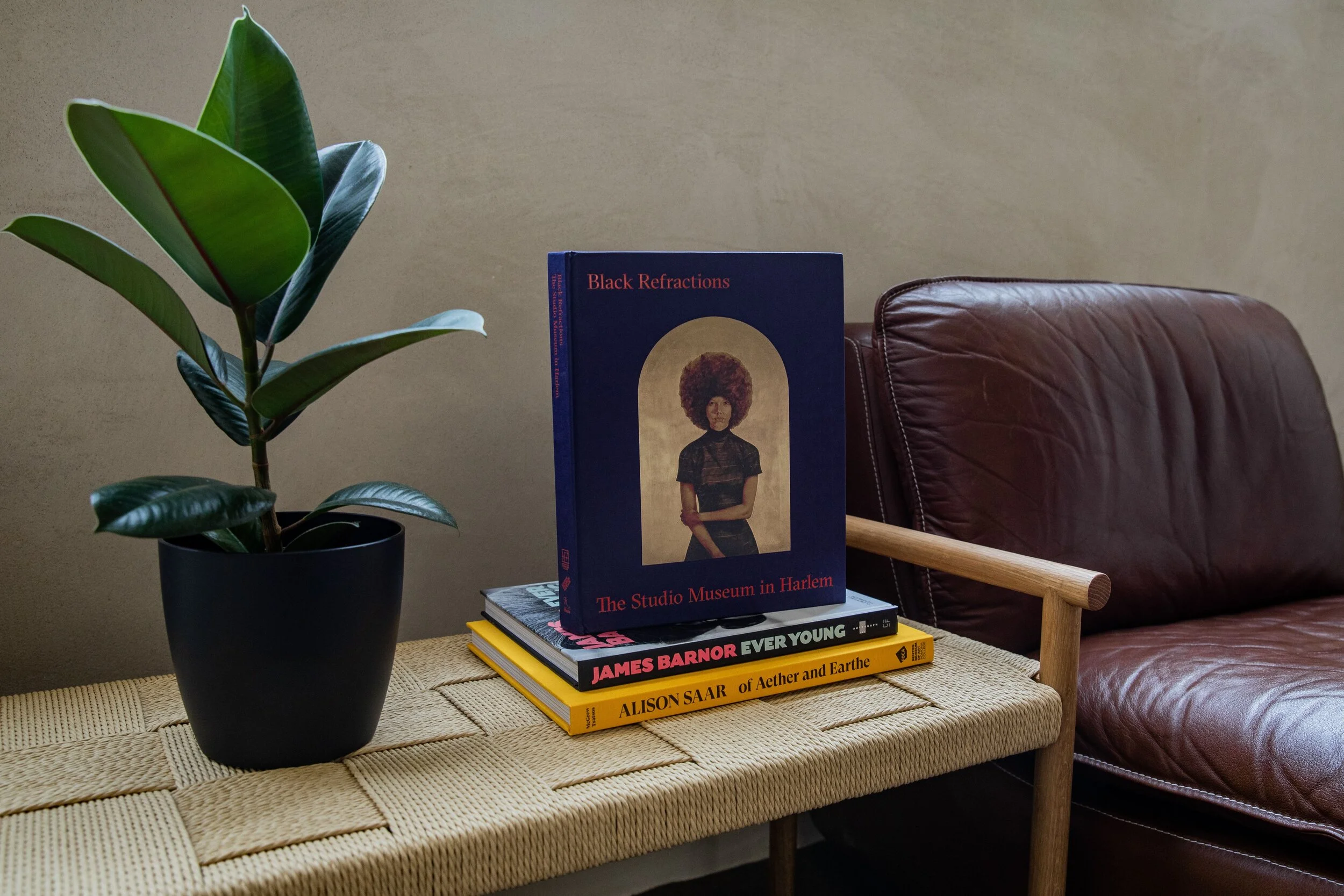

I’ve always considered ‘home’ a place of privacy—a safe haven and an invitation to rest, recover and reflect on other aspects of life. As a space and as a feeling, home and being home is a form of necessary self-care. So the first question I ask Ronan is simply, “How are you taking care of yourself?” As many might, Ronan admits to a lack of self-care over the past few months, noting an unhealthy imbalance between time spent working and space taken for rest and relaxation. She expands upon the importance of self-care for artists in particular. “I think downtime is so important for my own creativity and others’,” she shares. I recall my own understanding of self-care and am led to the million dollar question, “Why call your art space HOME?”. Ronan’s response takes me on a journey in itself. “As soon as I stepped in I was blown away by the space, the light, the ceiling height and the windows. It just really felt like home.” Guided by Caterina Bianchini’s Studio Nari, HOME’s visual identity is aimed at a sense of nurturing, self reflection, community and safe-space. Plants and candles work to settle guests while daytime photography studios and lounge areas cater to the artist and conversationalist alike. Textured clay walls are adorned for the wandering eye and currently spotlight Ronan’s own photography as well as the work of mixed media artist Joy Yamusangie.

“I am all too aware of the difficulties of navigating the creative industries as a Black female, and amongst the current offering in London, there needs to be a HOME.”

In presenting art not as some fenced off, pretentiously-priced exhibition, but rather as an enhancement of the space itself, HOME fosters a complementary relationship between the ongoing creative process and the allure of completed work. Ronan notes, “So often art spaces just rely on the work to show off the space and I wanted to counter that. I wanted the space to respond to the works and artist and give some context without any further explanation.” So how do these aspects of HOME work specifically to support Black and Indigenous creatives of colour? The answer is simple: by welcoming Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) communities to simultaneously create, observe and rest as and/or along with other artists of colour, as well as providing a safe space that validates one’s own culture and history. In an interview with Creative Review, Ronan reflects on the motivation behind the space and its value within London’s art scene, “I am all too aware of the difficulties of navigating the creative industries as a Black female, and amongst the current offering in London, there needs to be a HOME.” To outline the significance of her statement, I begin my research into the arts industry’s long history of excluding and exploiting creatives of colour.

From pricing BIPOC communities out of art ownership to presenting colonialist collections at museums and galleries, the art world’s elite and the institutions they oversee offer little to no space for creatives of colour to enjoy, exhibit or produce art. The Black Artists and Modernism (BAM) National Collection Audit is a research project led by Dr. Anjalie Dalal-Clayton determining the rate at which Black artists are represented in public collections across the UK. The study has found that roughly 2,000 works in the UK’s permanent collections were by Black artists and that most of these pieces remain locked in storage (though it’s important to note that the breadth of and motivation behind BAM’s work goes far beyond such statistics). When considering those 2,000 works by Black artists to the millions of artworks in some 1,500 art museums and galleries across the country, one cannot ignore the exclusion of Black art within the mainstream arts industry.

Image: Joy Yamusangie (left) and Ronan Mckenzie at HOME

Similarly, contemporary Indigenous artists of colour are seldom offered space in public collections. Just last year, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, USA, purchased its very first painting by a Native American artist. The painting, I See Red: Target (1992) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, is a response to colonisation and in many ways a landmark case for the American arts scene. It raises the question, “How in 2020, is this the first piece of contemporary Native American art that a national gallery owns?”

Where practice is made difficult by social exclusion within art spaces, one must not forget the proclivity of larger museums and galleries (and often those considered ‘educational’) to display inherently triggering works surrounding colonisation. Take the British Museum, for instance, an institution that has been repeatedly criticised for exhibiting stolen art and artifacts from across the world with little to no open conversation regarding the implications of such displays. Or the recent controversy surrounding a floor-to-ceiling mural at London’s Tate Britain museum, titled The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats (1927) by British painter Rex Whistler, and its depictions of an enslaved Black child, stereotyped images of Chinese people and additional scenes of racist violence. While institutions are often asked to remove these works, requests are repeatedly ignored or dismissed entirely, only given due consideration when faced with public outrage and petitions.

The prevalence of POC exclusion, white-washed collections and the colonised actions of museums, galleries and other art spaces are clear indicators of an oppressive, racist and elitist industry. Considering these aspects of the mainstream art world, how are Black and Indigenous creatives of colour meant to seek comfort or inspiration in such vehemently colonised contexts? The answer is simply that they shouldn’t have to—which is why HOME by Ronan Mckenzie is as vital as ever. In opening an art space that spotlights the work of Black and Indigenous creatives of colour while simultaneously offering them safe space and solace, Ronan opposes the exclusionary and colonial tendencies of the mainstream arts industry while prioritising the needs of marginalised creators of all racial/ethnic backgrounds.

In previous interviews, Ronan has referred to HOME as a space for “connection, community and intergenerational conversation.” As connotations may vary, I ask Ronan why these concepts are significant to her, her work as an artist and within her offering of HOME. She responds, “Feeling heard and seen is really empowering for me and I think for others as well—this is something that breeds through my entire body of work. Whether it’s photography, making clothes or film, collaboration and art provides a beacon of light and positivity. Especially through [the pandemic].” Her answer responds quite quintessentially to HOME, an art space created for personal, collaborative and creative empowerment and support. Ronan continues, “I think everybody craves connection [and] wants to feel part of something, part of a wider community.” In many ways, HOME is a call to action and a plea for more Black-owned, artist-led art spaces that do not exclude but rather encourage BIPOC communities to create and share their work without fear of judgement or intimidation. And Ronan isn’t the first to make that plea.

There is Autograph, an art gallery based in Shoreditch and directed by Dr. Mark Sealy MBE that champions photography and film exploring identity, representation, human rights and social justice; January Tamarind, curated by Khalid Wildman, a concept space and gallery for objects and design with roots across the African Diaspora; and finally I think of The Molasses Gallery, an open air art space promoting Black art-making, solidarity and unity. “There is an authenticity in Black-owned art spaces that other spaces cannot imitate,” says Tanaka Saburi, curator of The Molasses Gallery. “Black-led spaces want to live in an unmasked world where art approaches issues truthfully.” From proper representation to accessibility, these spaces are centres of connection to identities, cultures and histories rarely portrayed in the mainstream arts industry. By creating space for BIPOC artists and observers alike to witness, admire and be inspired by the work of their own communities, galleries like Autograph, January Tamarind and The Molasses Gallery are a beacon of a supportive rather than exploitative arts industry.

“The more HOMEs there are—the more places where Black and Indigenous creatives of colour can set up their own grassroots projects that we can all support and engage with—the better.”

Similarly, Ronan’s mission to provide safe, creative space to Black and Indigenous artists of colour does not begin nor end between HOME’s four walls. Through our conversation, she reflects on turning such an opportunity into reality, noting how HOME has and will continue to inspire and incite change both within and outside of the arts industry. “I feel so empowered to be able to have and offer this space. What I can do with HOME is even more special, for example, working with charities and organisations,” she says, referencing the space’s facilitation of and partnership with The Bibio Project, a clothing store that donates free children’s clothes and accessories to support Black families through winter. Ronan continues, “I want to show that [a space like HOME] is possible and hopefully inspire others to do the same. The more HOMEs there are—the more places where Black and Indigenous creatives of colour can set up their own grassroots projects that we can all support and engage with—the better.”

Our chat nearing its end, I turn my attention back to home. Not the space, but the concept. I ask Ronan to describe home in only one word. At first she hesitates, claiming one word is not enough. But what she lands on surprises me to say the least: “honesty.” In HOME’s countering of the exclusionary arts industry and its offering of safe and inspirational artistic space, it isn’t difficult to conclude that the work Ronan is doing is exactly that—honest. Even her admittance to a lack of self-care—as discussed earlier in our conversation—could be drawn back to this all-encompassing honesty and refreshing sincerity. To Ronan, HOME is not only a space, but a feeling—an honest and open embrace that is her community’s for the taking.

Learn more about HOME’s upcoming exhibitions here.

To get involved or book studio space (post-lockdown) visit HOME’s website.