Image: Even The Comfort Of A Stone Would Be A Gain by Nona Faustine

considering representations of black women in water as necessary symbols of joy, liberation and bodily autonomy

words Shaelyn Stout

For many marginalised groups, proper representation in mainstream media is a means of empowerment. Unsurprisingly, one demographic the mainstream has failed to properly represent is Black women. When we think of Black women in film for example, we are often faced with narratives of pain or oppression. Take The Hate U Give (2018), in which a young Black woman must deal with the loss of her best friend as a result of police brutality or The Help (2011), a film about two African-American maids working in the deep south in 1960s America. While such depictions reference important social issues, erased histories and systemic inequalities, it is time we portray Black women as joyous, free and in control. One way to do this is by representing Black women in spaces that empower rather than restrict. This essay will explore why water is one of those spaces and why representations of Black women in water are not only culturally and socially important, but also necessary.

Water brings life, as do women. To depict Black women in water is to emphasize their divinity, their autonomy and their strength. It is time Western mainstream media liberates Black women from exhausting narratives of pain by representing them in water—a symbol of life, leisure and higher wisdom. That being said, look to mainstream depictions of women in water and you’ll find they are overwhelmingly lacking in colour.

So why are we seeing so few Black women in water? The lack of representation of Black people, specifically Black women, in water is inherent to negative historical connotations and stereotypes of Black relationships with water and swimming. Assumptions that “Black people can’t swim,” for example, are rooted in years of legal segregation, systemic inequalities and the social and financial exclusivity of swimming spaces and education for Black and low-income individuals. Evidence of this is found in the relationships Black Americans have with public bodies of water, which have long been overshadowed by times of “whites-only” beaches and swimming pools preventing Black people from experiencing water peacefully and with bodily agency. Today, the remnants of this oppression lie in statistics like Black Americans aged 5-19 being five times more likely to drown than white Americans of the same age range.

It is important to note that these disparities are not exclusive to the United States. A recent report by Sport England found that 95% of Black adults and 80% of Black children in England do not swim. Statistics like this do not prove “Black people can’t swim” stereotypes right, but rather act as proof that Black people in the UK exist in a society that makes participating in such activities much more difficult for them than their white counterparts. Lack of affordability of and accessibility to swimming facilities and lessons, as well as the racial stereotypes attributed to Black people in water, are to blame for such disparities. The death of Shukri Abdi, a Somali girl who drowned in the River Irwell in June 2019, is a tragic reminder of how the oppressive attitudes many white Westerners hold against Black people and their relationships with water can have detrimental impacts on Black life. Though rooted in racism, such attitudes may also be influenced, in part, by a lack of representation of Black people in water or swimming within mainstream media.

Of the portrayals that do exist, Black men are often the focus. The importance of mainstream representations of Black bodies in water lies in their ability to combat negative stereotypes and allow Black audiences to see and believe in their own autonomy. But if these portrayals tend to centre Black men, how will Black women reap the same benefits? This is not to say representations of Black men in water are not important—they still provide Black audiences with themes of bodily agency, joy and liberation—but rather to ask why similar representations of Black women exist at far lower rates. The following scene from Moonlight (2016) shows Mahershala Ali (Juan) teaching Alex Hibbert (Little) how to swim, which confronts viewers with Black bodily agency in water, yet limits its reach to Black men.

Swimming scene in Moonlight (2016) featuring Mahershala Ali and Alex Hibbert

Audiences are faced with similar imagery in Burberry’s recent Christmas advert, in which a group of dancers make their way through a city and towards the beach to the tune of ‘Singing in the Rain’ by Nacio Herb Brown and Arthur Freed. At the end of the clip, Kevin Bago, the Black male dancer, runs ahead of the group and splashes into the ocean. He falls back into the water—arms spread wide and embodying a sense of freedom—as a long shot of his body depicts him gloriously in comparison to the crashing waves that surround.

While these visuals provide striking (and necessary) imagery of Black bodies in water, they still primarily centre Black men. This means of representation is clearly impactful, so why aren’t Black women getting similar screen time?

The significance of Black women being represented in water exists within considerations of intersectionality. Unlike their male counterparts, Black women face the double-edged sword of both racism and sexism and therefore deserve (and frankly, need) their own water-based depictions of freedom and self-empowerment. Such depictions aim to override outdated, racist and sexist media representations of Black women as ‘Mammy’ figures or sexually-deviant ‘Jezebels’ and show Black girls and women that bodily autonomy is one’s own. In other words, seeing Black women feel liberated in water is to believe other Black women can and should do the same. The recent casting of Black R&B singer and actress Halle Bailey (of music duo Chloe X Halle) as Ariel for a live-action remake of The Little Mermaid (1989) is an empowering example of this.

Bailey’s role as the first (mainstream) Black mermaid granted Black women not only the agency to exist in and enjoy water, but also to picture themselves in a role that’s only ever been reserved for white women. For once, the script had been flipped. Despite the significance Bailey’s casting held and still holds for Black women around the world, not everyone agreed with such a role reversal. As news of Disney’s first Black mermaid made its rounds, backlash ensued. The hashtag #NotMyMermaid brought forth countless arguments against the casting and even a Change.org petition hoping to boot Bailey and fill the role with a white, redheaded actress instead. The irony? One of history’s oldest mermaids was in fact, a Black woman: Mami Wata.

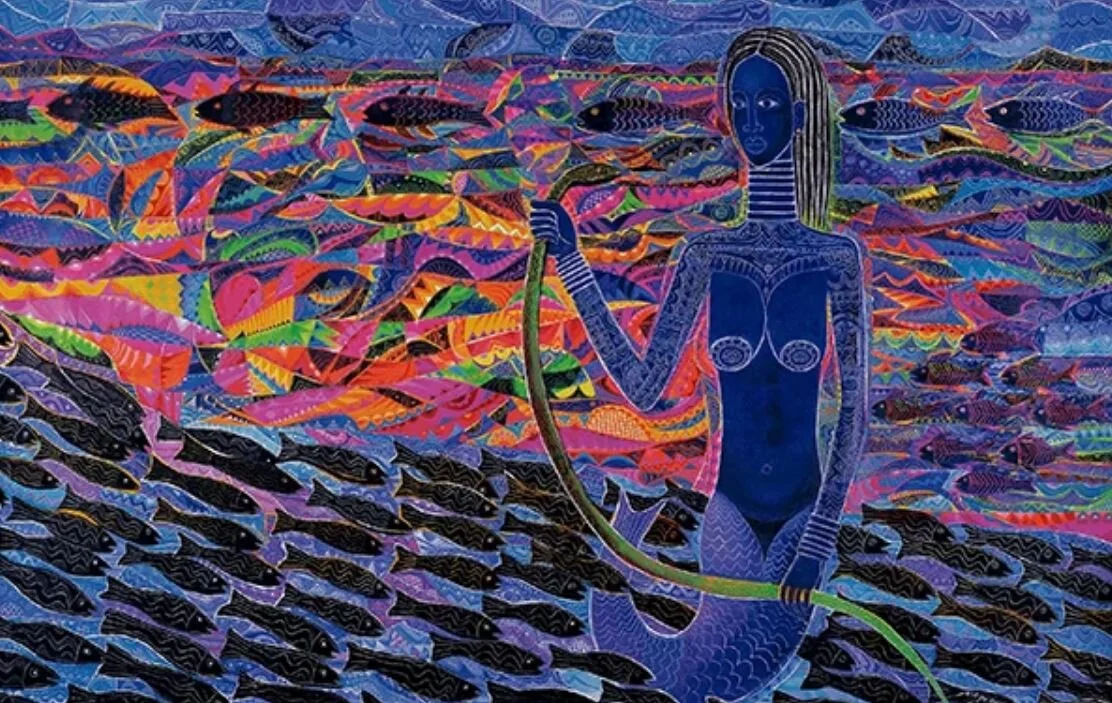

While harmful stereotypes of Black people in water were and still are spread throughout the West, the illustrious African spirit Mami Wata has been a culturally significant representation of Black women in water for thousands of years. Her origins can be linked to the Dogon people, an indigenous ethnic group from Mali and Burkina Faso in West Africa whose 4,000-year-old creation myth acts as a record of her stories and existence.

via The Fowler Museum at the University of California Los Angeles

Mami Wata can be visualised as part human, part fish or serpent, and is usually depicted in an ocean or sea—where she has made water her home. She has been described as a goddess of fertility, wealth, protection and seduction and is especially known for her striking beauty and healing powers. Tread lightly however, as Mami Wata may quickly turn evil if one approaches her for the wrong reasons. In most accounts, she meets her subjects by bodies of water and “brings good or bad luck depending on one’s character”. Seek her with love and modesty and she is said to protect, seek her for sexual misconduct or material gain and be smited. Sound familiar?

While whitewashed media continuously fails to portray Black women in water, Black artists of all mediums have taken on the task, reaching towards none other than Mami Wata to fill representative gaps and reclaim aspects of Black history often ignored and/or erased. In modern depictions, she has become a symbol of agency, resilience and power. One might say Beyoncé’s Lemonade, an ode to empowered Black women and at points, a smiting of her unfaithful partner Jay-Z, pays homage to Mami Wata’s divinity. In her ‘Hold Up’ visual, Beyoncé is initially submerged in water as her voiceover describes the denial she felt towards her partner’s infidelity. Later in the clip however, she emerges from the water-filled building—waves crashing out beside her—with a vengeance strikingly similar to that of Mami Wata. It reads, ‘fool me once, shame on you.’

The video continues and Beyoncé gets her revenge, symbolically smiting her partner’s wrongdoings by means of the well-known smash-a-car-with-a-bat tactic. In this case, viewers are presented with the agency and resilience of Mami Wata as well as the baptismal potential water holds for Black women.

Beyoncé — ‘Hold Up’ (Official Music Video)

Conversely, in visuals for ‘All Night’, Beyoncé could be mistaken for the water goddess herself, shown standing at the ocean’s edge as the lyrics, “nothing real can be threatened” narrate the scene. A tug-of-war scene between Beyoncé and another Black woman follows, their lower legs gracing the saltwater as a taut rope becomes symbolic of the singer’s previous tortures and newfound salvation found within her relationship. Here, audiences see the softer side of Mami Wata—one that offers kindness and humility—and are presented with the strength and beauty of Black women.

Such accounts of Mami Wata are not limited to the music scene. In partnership with Gucci and GARAGE magazine, creative duo Joy Yamusangie and Ronan Mckenzie recently created ‘WATA’, a visual “[exploration] of African ancestral myths and the power of dance”.

‘WATA’ by Joy Yamusangie and Ronan Mckenzie

The short’s use of story-telling, sound, colour and choreography work to depict the beauty and divinity Mami Wata represents. It simultaneously provides a representation of Black women in water that is rooted in African culture and tradition, which again, is not portrayed in whitewashed media. Yamusangie further describes the duo’s motivation behind ‘WATA’ as “a celebration and appreciation of our rich culture and African heritage, our freedom of experimentation, our lives in London”.

American visual artist and photographer Nona Faustine explores her own relationship with water and Mami Wata in her 2012 photo series ‘White Shoes’ and a 2016 group exhibition entitled ‘MAMI’. In ‘White Shoes’ her photo Like A Pregnant Corpse The Ship Expelled Her Into The Patriarchy presents Nona naked on the shores of the Atlantic, water gliding past her body as the sun beats down.

In ‘MAMI’, life-size cutouts of Nona’s naked body stand tall under golden capes symbolizing the wealth Mami Wata is said to provide. The salt and black heads on the ground surrounding could be Mami Wata’s victims, though Nona also wanted them to represent “the lost souls at the bottom of the Atlantic” as a result of Transatlantic slave trade.

Like A Pregnant Corpse The Ship Expelled Her Into The Patriarchy, Nona Faustine

In these examples, Nona’s imagery explores the lack of representation Black women have in discussions of myths and goddesses, which lends itself to an inherent lack of representation of Black women in water. Her work pays homage to water gods and goddesses as well as her ancestors lost across the Atlantic Ocean. Though she has not been met personally by Mami Wata, she explains feeling something—an indescribable feeling—when swimming in the ocean. To Nona, Mami Wata is reminiscent “of a place and time where [humanity was] intricately tied to the moon, stars, land and oceans”. Depicting and reimagining Mami Wata in her work empowered Nona as an artist, a woman, a mother and a human being.

“I thought of the incredible powers within Black women and tapped into the attributes that are within me. I also relished [in] the opportunity to interpret the Deity as beautiful and plus size.”

Nona Fuastine’s ‘MAMI’ installation, 2016.

Similarly, André Terrel Jackson, a Black, queer and non-binary artist from New Jersey works to honour and expand upon the African deity’s identity in their photo series ‘Mami Wata’. The series is a collection of André’s self-portraits by the ocean, their pose and gestures as empowering as the illustrious water goddess herself. Surprisingly, André only learned about Mami Wata after taking these portraits but quickly realised she resonated closely with what they were trying to portray in their series.

“Mami Wata is not of this world. She is not bound by our understandings of gender. As a non-binary artist that resonates with me. Through learning more about the spirit/deity I’ve learned to think differently about how I embody multiple ideas within myself. I think Mami Wata becomes who she needs to be, when the times call for her to be. [Likewise,] I celebrate the feminine that lives in me. The layers of meaning [in this series] and the questions they raise are filtered through the lens of Mami Wata.”

Self-portrait from André Terrel Jackson’s ‘Mami Wata’ series

Such depictions of Mami Wata and other Black women in water within mainstream (and not so mainstream) media act as a form of resistance against oppressive stereotypes while simultaneously working to enliven themes of agency and bodily autonomy for Black women. Inherently, these visuals also work to remind Black women of their own divinity and resilience in the face of racist and sexist narratives existing both in and outside of media and popular culture. Age-old spirits like Mami Wata prove that Black people, especially Black women, have enjoyed and been depicted in water for thousands of years despite a lack of appropriate representation today. Luckily, Black artists like Nona Faustine and Beyoncé, as well as deities like Mami Wata herself, continue to grant Black women everywhere the agency not only to exist in water but to seek and enjoy it.