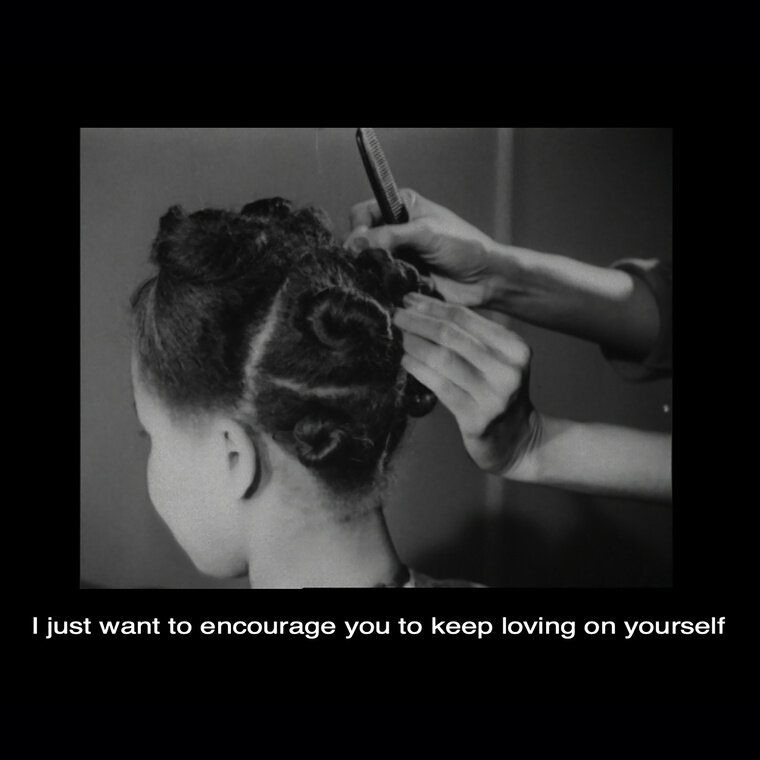

Still fromWhat Does The Water Taste Like? (2019) by Juliana Kasumu

Artist Juliana Kasumu on her film ‘What Does The Water Taste Like?’ and the complexities of British-Nigerian identity

In a live online event with POSTSCRIPT early December of this year, artist and filmmaker Juliana Kasumu screened her 2019 experimental film ‘What Does The Water Taste Like?’ and discussed her inspiration behind the project. As a deeply personal piece of art, the film explores the various movements and forms of tenderness that exist within the artist as she considers what identity, belonging and home mean to her, as well as how such concepts evolve with time. Separated into three parts (each section titled in Yoruba) and prompted by intimate conversations, ocean-made cyanotypes and archival footage, ‘What Does The Water Taste Like?’ questions the production of identity as it relates to the artist's own personal affiliations as a British-Nigerian and highlights the complex ways in which the past and present remain in constant dialogue. The screening was followed by a conversation held on Zoom between POSTSCRIPT Art Director Chinasa Chukwu and Kasumu examining the project in more detail and reflecting on the intricacies of British-Nigerian identity today. Here, we feature some of their discussion.

Chinasa: The film is split into three parts, Bawo lowa ore mi?, Kosi tun tun, and Mos’aro!. Can you explain what these titles mean and why you decided to organise the film [in] this way?

Juliana: The film was made over the course of two years while I was living in New Orleans to complete my MFA programme. I had left London to study in the US and it quickly became a very dark time. There was the whole homesickness thing and being distant from family, but also simply getting through the [MFA] programme was a lot more taxing than I had anticipated. My friends and I were trying to go back and forth to keep in contact with each other and we found that voice notes [were] the most convenient way because of the six-hour time difference.

One day my friend Sandra sent me a voice note asking questions like “How is the water tasting?” and I knew those questions were less about the differences between London and New Orleans but more about where I was [in life then] versus when I lived in London. That question, “How is the water tasting?” is how my film got its name. Looking back on those questions, I notice a bit of Nigerian Pidgin to them, but how I initially interpreted them was from this very Western perspective.

The beginning of the film is actually a conversation between myself and Sandra. This section is called Bawo lowa ore mi? which means “How are you, my old friend?” Pairing the recording you hear of Sandra and the archival footage of the woman having her hair straightened felt very intuitive, but again hindsight is 20/20. It looks to me now as this very intimate moment when you think about going to a hair salon and having your hair done, and comparing those feelings and sensations to what my conversations with Sandra feel like. So there is this layered element in that regard to the second part as well, Kosi tun tun, or “nothing new”.

Still from Bawo lowa ore mi?

Kosi tun tun is me, I am discussing myself and my relationships with my names. Juliana is very much still my given name; it’s on my birth certificate. Tosin is how my intimate family knows and refers to me as. Growing up there was a lot of rejection that I experienced, specifically when I was granted the power and the agency to decide what I wanted a new group of people to recognise me as. Back then it felt like the easier my name was the better. Now I’ve reconciled that Juliana has become a more distanced outsider while Tosin remains a very intimate part of who I am. I recognise and accept [Tosin] differently than I did when I was a child.

The third part of the film is Mos’aro! which means “I miss” or “I miss you.” So the last conversation is between me and my mum. That was also very intuitive because the conversation I had planned to record with her is not the one I used in the film. Instead she had remembered a Whatsapp message I sent her a couple [of] weeks prior asking her to translate something for me. And so she was like “Ok, well you’re going to learn to say this yourself.” We often have those back and forths where she is trying to teach me Yoruba words or I’ll be blaming her for my not being able to speak Yoruba well. So for that moment when things feel tender and funny, there is also a sort of acknowledgement of the things that have been lost and of the space between us. No matter how close I get to my mum, there will always be that element of us not being able to understand each other because of the language barrier. I love listening to that section and hearing her laugh, but Mos’aro! is also a testament to unlearning. The whole project What Does The Water Taste Like? is about my process of unlearning.

“No matter how close I get to my mum, there will always be that element of us not being able to understand each other because of the language barrier.”

It’s amazing to hear more about these sections and how they came together in your project. Each part seems to represent the different experiences and people that lead you to this unlearning, from conversations with friends, to yourself and finally your mum. Moving back a bit to Bawo lowa ore mi?, why did you juxtapose the vintage video of hair treatments with the message of self-love?

I think I wanted that feeling of comfort. I had become used to creating art about others and externally, but for the first time, I was in a place where I had no family or friends. So I became the object of my work. Thinking about that intimacy when you do have your hair done—I can only speak for myself but I don’t trust anyone with my hair. Maybe that is more the West African spiritual superstition of “be careful who you let touch your hair because you don’t know what energy they are bringing to you.” When I think about having my hair done though I think about intimate moments, I think about what feelings are shared and the trust those people have with each other. And so I think that footage mirrored the trust you share with a friend like Sandra. There is still the idea of unlearning though because the woman is having her hair straightened and ironed out. It’s a balance between conflicting ideologies because there is still love in that process and existing between those two people.

Still from Bawo lowa ore mi?

I think that’s such a beautiful representation of the choices our parents had to make, for example, in deciding whether or not to teach us our traditional languages. There is always the understanding that whatever choice they made, it came from love and your parents need for you to be accepted and have an easier life. In the second part of your film Kosi tun tun, we meet the model at a hair salon but it’s not to change her hair. Rather she leaves with a big untouched Afro which implies that things are changing. However, the juxtaposition again with the painful story of changing your name to fit in shows that there is still so much progress to be made. Is that what you intended to show?

What I love about this project is that I know what it means to me, but I am always awed by what happens when other people look at it and what other people see in it. When I think about the process of my name changing and about the things I have accepted, unlearned and even forcefully rejected, I think about having this woman who exists in a world she rejects, but who also knows there is so much to be done. For example, I have [a] friend who is a filmmaker and who sent me his storyboards. The sections had all these little white stick people and he didn’t even recognise that. It became this really funny conversation about “why is it that this film is supposed to be about Black women but your storyboard is reflective of white people?” So I think about what I wear, how I dress, how I choose not to dress and what languages I use or don’t use and I remember that there is still work. We have to stay introspective as painful as it may be.

I often mute the part about me changing my name when I watch the film because that admittance, even if I was only nine or ten years old at the time, is difficult to hear in retrospect. It still affects how I introduce myself today because I can say “I’m Tosin”, but then I question if that name connects me to Juliana Kasumu the artist. It’s like living in two different existences because again, when I come home I am always Tosin Kasumu. I’ve even had to learn and teach two different pronunciations of my last name depending on where I am. So yeah, it runs deep. But I’m excited to be on this journey—I’m excited to start confronting those behaviours and making the conscious, everyday effort to start unlearning them.

“When you think about Yoruba names and how they signify the importance of spirituality, the importance of culture or even the effort of learning their pronunciation, those are all of the things I rejected. So it shouldn’t feel empowering for someone to call me Tosin but it does sometimes.”

Why was that experience of having your name butchered such a searing one in your memory?

Looking back, it was definitely a rejection of self. When I remember that moment I remember it not being the first or the last time my name had been butchered. I remember that whole week of school, everyone had somehow found out and so everywhere I went on the playground or in class the rejection of my name followed me, which you hear about in the film. When I had the choice and the power to choose my name at the beginning of the school year and I sat down to write Juliana, my mum said “and Oduduwa Tosin” [implying] don’t forget that part. That moment in the classroom, however, gave me the agency to say, “I’m Juliana and you can cross the other name out.” Looking back, I acknowledge it was a rejection of myself, my culture and the importance of my name. When you think about Yoruba names and how they signify the importance of spirituality, the importance of culture or even the effort of learning their pronunciation, those are all of the things I rejected. So it shouldn’t feel empowering for someone to call me Tosin but it does sometimes. That's where we’re at; that's where I'm at. I know I’m centred and I know Tosin is my name.

The story about changing your name is one that resonates with me. Both my first and middle names are Igbo names. Of those names, I chose ‘Chinasa’ since it’s easiest to pronounce. So I’d say your story resonates particularly with British-Nigerians, but also with other children and people of colour who have been told that their names are too difficult to pronounce. Did you set out to make a film about these realities or did the project simply morph into that while you were making it?

It literally just morphed into that. Even as you’re speaking I think about how Juliana is my name: it’s on my birth certificate, it’s the name I was christened with. But more than that, it’s a European sounding name accepted in [Western] society. I’m not trying to speak to a specific theme in [this film], so what I find beautiful is when people who may not know you as an artist or a person can still feel connected to you and your work. It’s a sort of reference to this idea that you are not alone in your feelings and sentiments.

Still from Kosi Tun Tun

In reference to Mos’aro!, I recently read a study on British-Nigerian identity and some of the subjects noted that their parents had purposefully not taught them any traditional languages so they could assimilate better without the burden of having an accent. Why does the character in your film decide to learn Yoruba? Was there a moment you decided it was something you had to learn or did it come over time?

I would say that it was something I’ve been feeling for a long time. When I was in [the] first year of [university], I read Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and I remember being in awe of this woman who created a fictional Nigerian war in the 1960s. I told my mum about it and all the sudden she had all this information about the actual war and how she was seven or eight years old when it happened. So I think the shock of not knowing that this part of Nigerian history existed is what made me want to learn more about where I came from. It was like, what else don’t I know? That, for me, was the shift. It made me want to be more connected with my culture. I remember the first time I went to Nigeria at around 17 [years old], I felt so frustrated with being unable to speak to my cousins. Again, it’s comparable to my relationship with my mum. There are many times we forget each other's language and so it creates this constant shift of understanding between us. The way to stop a culture from thriving or being passed on is by first taking away the language so stories and ideas can no longer be passed down. Thinking about my mum and how no matter how close we are our relationship will always have a slight disconnect because of language is why [Mos’aro!] was created.

Final question, what did the process of creating What Does The Water Taste Like? teach you about your identity?

It solidified [the] thought that as much as I think I know about my identity, I still know nothing. It sounds weird but I need to remind myself of that every day no matter how humbling or draining it may feel. Working through this project, both the film and the original installation, I realised all these questions I had may not be answered in my lifetime or even my children’s lifetime. It’s still important to keep looking for answers and continue having those conversations because that’s the only way you ever truly get to know someone. But yeah, I don’t know as much as I think I know is what I’m getting at. Identity is this forever shifting thing.

*This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.