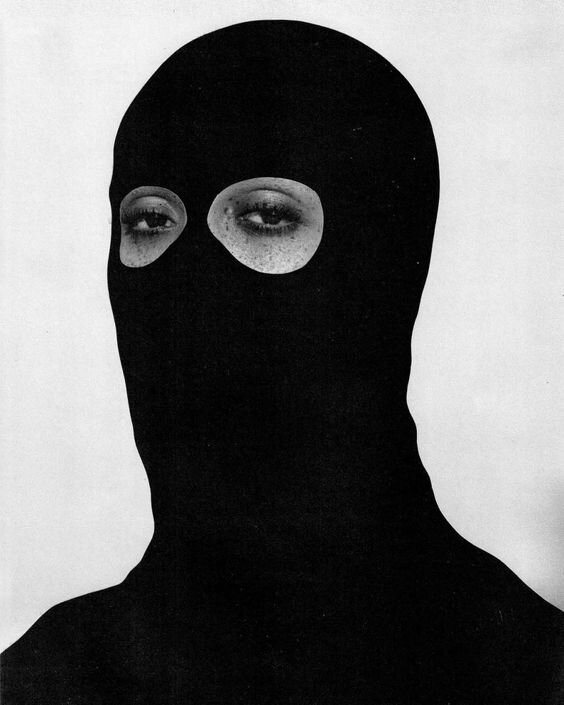

Image: Jesse Draxler

How is ‘crime and punishment’ used to maintain disparity in society, and therefore a hold over those the State benefits from marginalising?

words Roxy Legane

In the UK, for most of society who are unlikely to encounter the criminal justice process, it is easy to disconnect from its functioning and conclude that punishment is served to those who ‘deserve it’ and policing and prison keep the ‘law-abiding’ safe. This essay critiques that summary, drawing on under scrutinised areas of criminal ‘justice’, black and brown young people’s experiences of state violence, psychological harms and the tools that perpetuate an unjust system. It will explore how in a deeply unequal society, ‘crime and punishment’ is used to maintain disparity and therefore a hold over those the State benefits from marginalising.

In 2019, Manchester-based community project Kids of Colour hosted the event ‘Kids of Colour on Policing’ in collaboration with Northern Police Monitoring Project. Throughout, young people on the panel shared their experiences:

‘They started with this ‘police knock’, which until this day still haunts me. For years, whenever any door would knock, in anyway similar to this ‘police knock’ I would cry, shake, run or hide’

(Young Person, 17, Kids of Colour)

The above quote, an account of post-traumatic stress disorder, is not isolated. In fact, it is one of many accounts that exist as a result of excessive policing across the UK. Trauma triggered by state violence remains a neglected concept, particularly when it comes to the over-policing of black and brown young people; a demographic lacking public empathy. This oppression, enabled by the support of our government, is becoming increasingly validated as plans arise for 20,000 more police officers, enhanced stop and search powers and the extension of taser use. All of these ‘solutions’ – often implemented without prominent critique – are a nod to continue the normalised control that etches away at the resolve of young people who reside in areas facing inequality.

Excessive, racialised policing acts as a daily reminder to the individual and their community that they remain regulated by the State, their bodies and mind not belonging to them. Individuals are open to exploitative intrusion on any given occasion, for things as everyday as walking down the street. An account recently shared with me of police violence following “mistaken identity” evidenced just how significantly these abuses affect mental well-being; a 14-year-old black boy telling his mother that ‘if the police want to kill him, they may as well get on with it’. Experiences like these must call into question the purpose of our criminal justice system. When it causes unending harm to populations the State has long sought to ostracize, how much are we willing to condone? In cases of over-policing, it is important to recognise that it is not crime that is being policed, but young people’s lifestyles and movements to continue a one-sided war of attrition.

Take the London Metropolitan Police’s Gangs Matrix, labelled by Amnesty International UK as ‘a racially discriminatory system that stigmatises young black men for the music they listen to or their behaviour on social media’. Through discussions with those who have been labelled as ‘gang nominals’, Stopwatch’s Being Matrixed: The (Over)Policing of Gang Suspects in London represents:

‘what it is like to live in a police state, where police surveillance and intelligence gathering function of the multi-agency gang management units conspires to curtail opportunities for young black and Asian people under a guise of safeguarding and risk- management’

Young people are being subject to excessive policing that limits their movement as a means of social control, irrespective of whether they belong to a ‘gang’, far more interested in the policing of identity, interests and culture. Very little attention is paid to the harm caused to young people at the receiving end of this kind of enforcement. Ultimately, it would require the majority to accept that state violence administered through the hands of the police exists; a truth still silenced in this country. But attention is necessary, and as argued through the report, the harm created as a result of intelligence gathering, combined with the violence exerted by the police, is in fact ‘criminogenic and crime causing’.

Image Source: Complex

Widespread action against the flaws that define policing and punishment in this country would require a more transparent discourse than that featured in mainstream discussion. As that does not exist, it is fundamental that each of us works to educate ourselves as to whether our idea of justice is being met. The use of tactics such as stop and search to reduce crime remain ineffective, yet combined figures for England and Wales show black people are 40 times more likely to be stopped than white people. Many argue that the excessive use of such powers works to condition selected populations for prison. The reactive implementation of crime control tactics will always have problematic effects; such as solidifying the next steps in the school-to-prison pipeline.

As the UK remains simplistic (and arguably ill-intentioned) in its approach to tackling knife crime, leaders call for more schools-based police officers in areas at ‘higher risk of youth violence’. Mirroring action taken in the US, where ‘over 40 percent of all schools now have police officers assigned to them, 69 percent of whom engage in school discipline enforcement’ [1], the detrimental impacts are either not considered, or welcomed. What will it mean for young people who remain fearful of their over-policing on the street, to see officers inside the school gates? How much more oppression will black and brown young people face when multi-agency working is underpinned by (mis)intelligence taken from school? A space that should be a sanctuary for learning.

From my master’s research into schools-based police officers in Manchester, the idea that these draconian measures will reduce crime is easily contested. Reflecting gangs databases (and contributing to them), the intelligence gathering that will take place in the school corridors will support the creation of subjects to be policed, who will later fill the expanding prison complex. When reflecting on developments in education, the growing likeness to prison (isolation booths, zero-tolerance policies, police officers, knife arches) is stark, and therefore the process of criminalising young people before crime has been committed cannot be ignored. Karen Graham’s chapter The British school-to-prison Pipeline in Blackness in Britain makes clear this process, detailing the way schools:

‘identify, isolate and then ‘train’ a minority of their students to fit the future role of imprisoned offender. Though certainly notalone, Black Caribbean boys are more likely than any other group to fall into this category’

A schools-based police officer will be another cog in the process of criminalisation, a tool that perpetuates young people’s feeling of being controlled, seeing them internalise the belief that they are on course to meet the label they have been dealt. This process of criminalisation is well documented in American research into the criminalisation of Black and Latino young men in education and beyond [2].

Moving from the community to the prison system, when considering excessive punishment and the trauma that ensues, individuals ‘Imprisoned for Public Protection’ are not far from thought. Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentences, introduced in 2005, see individuals sentenced to a minimum time period with the caveat that release awaits approval from a parole board. Put simply, the sentence is indefinite. Although IPP’s were abolished in 2012, that was not done retrospectively. Individuals like Wayne Bell, imprisoned at the age of 17 for stealing a bike and assault and who is still inside now, aged 29. The Prison Reform Trust’s 2010 publication Unjust Deserts: Imprisonment for Public Protection stated that ‘IPP prisoners appear to suffer from significantly higher rates of mental health problems than other prisoners’, along with a higher rate of suicide than the prison population as a whole.

Enforcing punishment to achieve a better society is nowhere near the mission of this sentence, or the mission of sentencing and prisons in their entirety. Gangs databases, schools-based police officers and IPP sentences could well be seen as the extreme end of criminal justice, but they draw attention to a deeply problematic system: one that has allowed them to flourish. Given the origins of British policing as a means of ‘managing disorder and protecting the propertied classes from the rabble’ [1] and the success prison has in disproportionately holding people of colour and working class communities, the disparities so often ignored must be seen for what they are; intentionally discriminate. As Gilroy’s There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack shares, ‘explanations of criminal behaviour which make use of national and racial characteristics are probably as old as the modern judicial system itself’. When we lock up more black people proportionately than the United States; fewer than 1% of all children in England are in care but make up two-fifths of children in young offender institutions; and over half the women in prison have reported being victims of domestic violence [3]; it is clear that the prison system is not fit for purpose or a solution to ‘crime’. Policing and punishment are diametrically opposed to achieving equality and a radical re-think is in order: not just one limited to reform.

It is evident that we will struggle to instigate meaningful discussion around abolition. Bizarrely, a society being one without the need for police or prisons is dismissed as ludicrous, instead of being an ambition. Conversations stop at the first hurdle, to even think about an ideal society is an absurdity. Instead, we resign to one that locks human beings in cages, because alternatives to punishment, a society with no prisons, and one that has housing, education, employment, healthcare and welfare that works for all is apparently a romanticised pipe dream. As Community Action on Prison Expansion state, we must ‘seek alternatives that keep our communities safe and achieve real social justice’, instead of accepting a society that perpetuates inequality, creates deviance, and finds solutions by instigating further trauma and harm through its punishment practices.

Made clear by Angela Davis [4], solutions reside in challenging society to consider three key questions: 1) How do we move away from a prison system that is increasingly led by corporate profit? 2) How do we dismantle narratives and processes that centre race and class as definitions of deviance? 3) How do we progress from needing punishment to feel that justice has been served? Ultimately, as Davis states, it is imperative that we commit to creating institutions outside of the criminal justice system that are ‘vehicles for decarceration’, if we are committed to a just society.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

Alex S. Vitale (2017) The End of Policing

Victor Rios (2011) Punished: Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys

For information on the prison population – Prison Reform Trust: Bromley Briefing Papers

Angela Davis (2003) Are Prisons Obsolete?

Essay originally featured in POSTSCRIPT Issue 3.

ROXY LEGANE is a community campaigner and the founder of Kids of Colour: a platform for young people of colour to explore their experiences of race, identity and culture in modern Britain and challenge everyday and institutionalised racism.