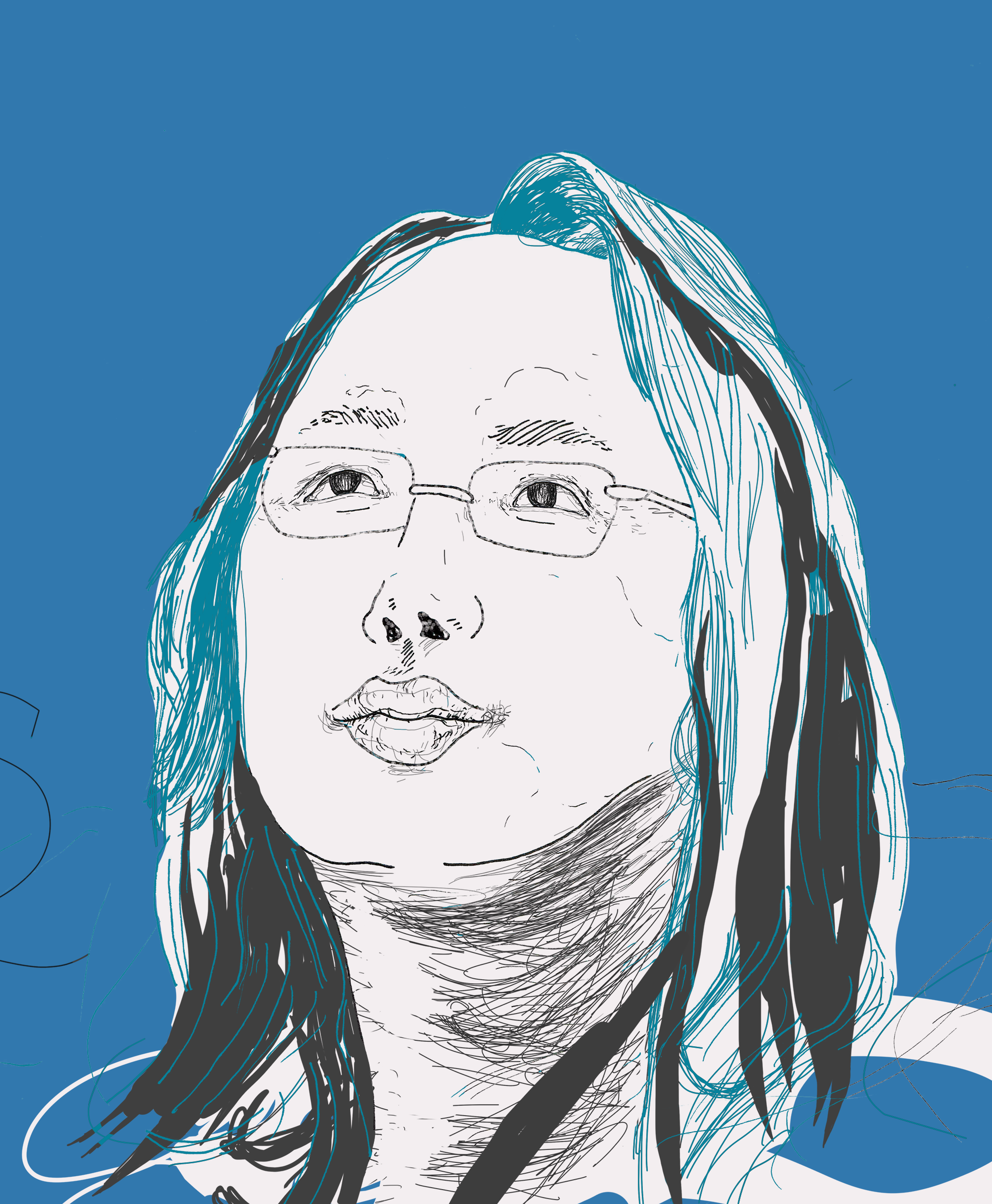

The first digital minister of Taiwan, Audrey Tang, on her journey from hacktivist to politician, radical transparency and the effectiveness of social outrage

“I started programming when I was eight years old, and I started without a machine. I just had some programming books on the bookshelf, I think from my uncles, and I just started reading it. We didn’t have computers at the time, so I just took [an] A4 [sheet of] paper and split it in half, and drew on the bottom half a QWERTY keyboard, and started mock typing on it and writing the computer’s responses and so on. Of course, after a couple [of] month[s] my parents kind of gave in and bought me a personal computer. But that’s how I learned to program when I was eight years old, that was 1989”. This anecdote about her childhood, dropped casually into the conversation is just one example of the self-education of Audrey Tang.

While teaching herself programming, Tang decided to leave formal high school education at fifteen-years-old to pursue a more extensive learning experience. Contrary to expectations, the decision was supported by her principal. “I remember distinctly telling my principal at the time that instead of going through the university, college, post-doc, and so on, I actually wrote emails to the leading researchers of the field asking for clarifications. My principal heard that story and thought about it for a minute and said, ‘OK, from tomorrow on you don’t have to go to school anymore, and I’ll cover for you’”. This willingness to bend the rules to find a more suitable path for her student, Tang says, instilled optimism in her regarding flexibility in bureaucracy. Part of this self-education was a close reading of written classics which she accessed due to their availability on The Gutenberg Project. She also attributes some of her optimism to the fact that these were written before WWI and as such had not taken on the despair and dystopian tones of post-war writings.

From anyone else, this reasoning of childhood influences might seem an oversimplification. However, Tang delivers the analysis in an almost conversational tone that marks it as a concise observation where she just happens to be the subject. She seems to have a memory of near-perfect recall. Throughout our hour long conversation, she responds with a date and context reference for nearly every question. Recalling the specific year and occasionally even the specific software she would have been working on at the time.

ON BEING TRANSGENDER

Tang’s overall philosophy is underpinned by the aforementioned optimism. Asked about her experiences as the first transgender minister in the world and the potential effects it has on her working relationships, she is quick to jump to her country and colleagues defence. “Taiwan is especially inclusive and tolerant”, she notes, pointing out that due to the country’s comprehensive approach to gender inequalities -they carry out gender impact assessments on every single policy and draft- she feels supported. She emphasises that the issue of gender equality is of such import that their gender equality committee is designed so that they have exactly one more seat than government ministers in the event of a vote. She is also quick to point out that though she is seen as an outsider advocating for the next step in gender mainstreaming for the post-gender age, it is built on a feminist movement. As a result, she has a large community in the mainstream of public servants that support her. “It’s not like I’m in the minority, literally every public servant in the past 12 years supports my mission.”

“I think having gone through two puberties, really helped [my] communication. It gave me a perspective of intersectionality. Meaning that although I do have my privileged positions, I also have my vulnerable lived-in experiences.”

Yet she is aware of the influence it has had for her both personally and professionally. “I think having gone through two puberties, really helped [my] communication” Tang explains. “It gave me a perspective of intersectionality. Meaning that although I do have my privileged positions, I also have my vulnerable lived-in experiences”. As a result of this, all decisions, policy and otherwise are approached from an empathy base. Before policies are decided, she seeks to understand not just the technicalities of potential new implementations, but also the emotions of citizens comprehensively quantified through an online forum.

FROM HACKTIVISM TO POLITICS

Her expansive approach to policy making is rooted not just in her experiences with gender but also in the route she took to arrive at politics. Having participated in the free software movement early on, she became involved with Silicon Valley by fixing issues on open source platforms before becoming a consultant for companies such as Apple. Discussing whether there was a particular strategy for seeking out work as a nineteen-year-old self-taught programmer, Tang states “the work just found me”. She acknowledges this was in part because she had published over a hundred reusable software components and had received thank you emails from the BBC and the Human Genome Project amongst others. During this period, however, she reveals that she worked as a liaison or “branch point between the two bodies” of the digital movement and the government.

Whether due to her experiences with gender or finding herself in foreign spaces in her youth, being a branch point comes naturally to Tang and is what she credits with her ability to transition from protester to policymaker. “Buckminster Fuller said it best, ‘instead of fighting against an old system, make a new one that makes the old one obsolete’. That’s exactly what I’m doing”. She sees her role more as a connector between the people and the government, focused on making space for experiments on alternative governance systems to see what might be a better option for existing models. She also has the backing not just of her department but of the government as a whole, noting that while she came in under Jaclyn Tsai, who she met while she was hacking as part of the Sunflower protests -a movement which saw groups protesting overall for more citizen participation in multiple areas including constitutional amendments- the new minister Doctor Tsai, has continued the work and has made digital economy issues subject to public nationwide debate. Though Tang came into politics after the events of the protests and essentially from a position that was ‘anti-establishment’, she doesn’t see her relationship with her colleagues as particularly tense and finds that they have been welcoming. “For them, it’s risk reduction. It’s also improving their efficiency so they can actually get home earlier”.

RADICAL TRANSPARENCY

An interview request sent to Tang is met with a link to her radical transparency protocol where you are informed that in order to interview her, you must be open to having your conversation recorded and published for public consumption. This is part of her endeavours to create more transparency in the way governments work to encourage more public engagement and civic participation. The process involves the utilisation of online technology through their platform g0v (pronounced Gov Zero) as a way to amplify and connect the voices of citizens on certain topics. Unusually, the platform also includes an emotion rating which shows not just what the votes are on particular issues but also why individuals have voted that way and how proposed policies made them feel. Their engagement is one that Tang accords the utmost importance. She points out that in Taiwan “we have broadband as a human right” and states emphatically that “anywhere in Taiwan if you don’t have 10Mbps, it’s my fault. You can talk to me.” She is quick to point out that these online participation tools do not replace face-to-face meetings with constituents. “We never ask people to come exclusively to the digital. Digital is just a way to determine the agenda [for the next face-to-face meeting]”. Here, in the unlikeliest of places, Tang’s understanding of human interactions is highlighted as she underscores the significance of 1080p high definition video as part of the data collection process. She explains that its import lies in the inscrutability of micro expressions at lower definitions which affects the ability of users to interact with one another and in the long run diminishes trust amongst participants.

Radical transparency also has limits. “I told the National Security Council, ‘don’t tell me anything that is a state secret!’” Tang laughs. She clarifies that the aim of a radical transparency policy is not to make all information immediately available but rather to operate from a position where transparency is the default which then requires an extra effort to redact. She also discloses that the policy does not operate in a vacuum. As the reach of the policy continues to extend there are larger considerations to be met. Using indigenous nations as an example, she underlines that, “the democratic principle is very simple. If something is systematically in the minority, as defined by intersectionality principles [it] should not be put to a popular vote”. Pushed on whether their radical transparency and civic participation policies are similar to China’s Social Credit system, Tang smiles and eloquently points out their differences saying, “what we’re doing is making the state radically transparent to the citizens. What they are doing is making the citizens radically transparent to the state”.

A NEW APPROACH

In a ‘post-truth’ age where some see ‘PC’ culture as detrimental, Tang sees social outrage as a useful tool. She delineates the differences between “personal anger” which comes from personal offence and“social outrage” which unites rather than divides people. Social outrage she notes can lead to finding a “common cause” amongst areas of disagreements and moving forward in contrast to personal anger which seeks consensus. With the former, “if we keep meeting, we will reach something that we can both at least agree is factual. That is the foundation of conversation”.

How can citizens from other countries hold their governments and industries to account and implement the same policies? “I think it’s easier if you start with a level of governance that is smaller scale” Tang says. Throughout our conversation, it has been evident that for her, the nexus of change is in the ability to connect with one another on shared “similar lived experiences”. She notes that often “ideologies mask common concerns”, so citizens should start in their local precincts and city council, if possible, she even suggests they start “without the public sector, you can just run it in your co-op”. She is also quick to point out that while Taiwan may be seen as particularly progressive, their progression stems not from any technological advancements or contributions but instead from how they operate that technology, that is to say, “not on the fringes of the governance apparatus but rather at the core of the governance apparatus”.

In true radical transparency form, our interview ends with Tang asking whether I would like a written transcript or a video recording of our interview to be made available for the public. One of my last questions to Tang is what drew her to g0v? she responds that it was its simplicity. A simple domain hack changing an ‘o’ to a ‘0’ taught her that “if I don’t like the government, I can do better”.

*Editor’s Note: This article was revised on Nov 27th, 2019. A sentence was incorrectly repeated twice in print, a mistake made during the design process. It has been amended here. The interview was originally featured in PS Issue 3.