Image: Ngadi Smart

Rafeeat Aliyu considers her role in and the importance of sharing queer women’s stories from Nigeria and West Africa.

words Shaelyn Stout

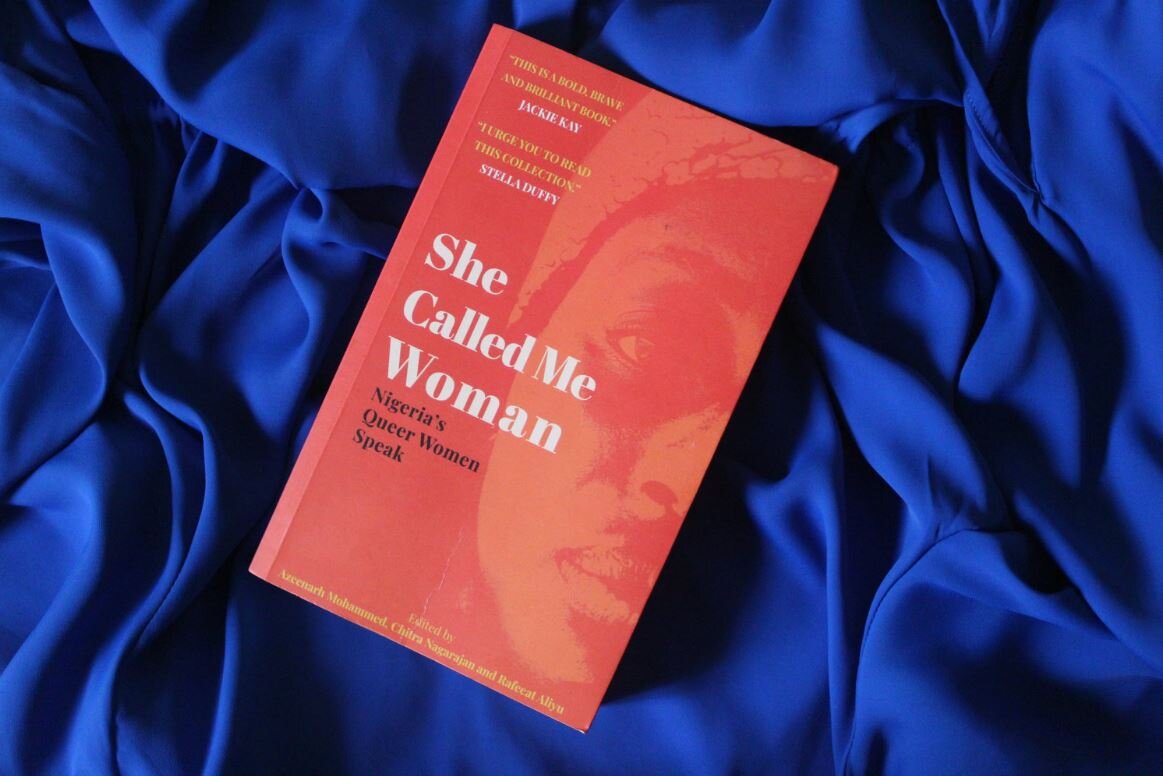

Rafeeat Aliyu is a writer, editor and documentary filmmaker from Nigeria whose interests lie in gender, sex and sexuality as well as history, culture and how all of these topics intersect. Her work editing She Called Me Woman: Nigeria’s Queer Women Speak conveys a dedication to queer representation in Nigeria and West Africa while offering important and deeply personal narratives from the region that must be shared. In our interview, she told me more about She Called Me Woman as well as the compassion she has for Nigeria’s queer women and why it’s important to hear their stories.

Image: Shayera Dark

Shaelyn: Can you give us a brief introduction to your work in She Called Me Woman: Nigeria’s Queer Women Speak?

Rafeeat: She Called Me Woman is a collection of true stories from queer Nigerian women. We use “queer” here as an umbrella term to cover the bisexual, lesbian, trans and queer women whose stories make up this collection. She Called Me Woman grew out of a desire to see women’s stories from Nigeria told like the ones we were reading from other parts of the world. I am referring to books like Bareed Mista3jil by Meem, a collection of narratives from queer Lebanese women, and Tommy Boys, Lesbian Men and Ancestral Wives: Female same-sex practices in Africa by Ruth Morgan and Saskia Wieringa, in which authors from eastern and southern Africa collected and analysed narratives from women involved in same-sex relationships/practices.

Reading books like these made me long for something similar from Nigeria and West Africa. Luckily, my co-editors Chitra Nagarajan and Azeenarh Mohammed felt the same way and with support from Cassava Republic we were able to turn our dreams into reality.

“I am a firm believer in the idea of sankofa, or looking back to learn in order to move forward. I think it’s important to keep African approaches to [sex and sexuality] alive”.

What inspired your interest in these topics and why are they important now?

I have always had an interest in gender, sex and sexuality. Initially, I expressed this on my blog (cosmicyoruba.xyz) where I’d write essays on women and society from West African history based on research I did in my free time. I was very interested in the lives of the women that came before me. When I learned about practices like initiation rites and woman-woman marriage, I became so fascinated that I simply had to share.

These topics are important to me now because I genuinely believe it’s necessary to understand where we came from. I am a firm believer in the idea of sankofa, or looking back to learn in order to move forward. I think it’s important to keep African approaches to [sex and sexuality] alive—whether we agree with them or not—so histories are not forgotten and so we don’t repeat past mistakes.

Reflecting on what you were taught about sex and sexuality growing up, how have those teachings impacted your understanding of your own identity and your opinions of Black sexuality and sexual agency?

Growing up, I was never taught about sex and sexuality. I went to a Catholic school and what I recall from there was basically being told not to have sex—to aspire to be a virgin until marriage. I remember writing something along those lines in the diary I kept as a teenager. Regardless, I’ve always been a curious person and when I was given the opportunity to learn more [about sex and sexuality], I pounced.

Image: Ngadi Smart

As a nerd, my exploration [of these topics] was different than most. I spent hours in the library reading all I could on the subject of sex and sexuality, slowly narrowing down until I found academic works that specifically addressed sex and sexuality as it concerns Black women. I remember devouring books like Gloria Wekker’s The Politics of Passion: Women’s Sexual Culture in the Afro-Surinamese Diaspora and Sylvia Tamale’s African Sexualities: A Reader which introduced me to the concept of Osunality in Nkiru Nzegwu's chapter, Senseisha: Memoirs of the Caribbean Woman, an anthology of stories about positive female sensuality from Caribbean women, the Sexuality in Africa magazines and more. Reading these books years ago impacted my own identity by letting me know that it [was and still is] okay for Black women to be sensual and own their sexual agency.

Historical portrayals of Black women often strip them of their agency in relationships with pleasure, desire and both sexual and non-sexual identity. How can Black women reclaim that agency and become closer with their sexual selves?

I have a different approach to this because I sought out the historic portrayals that did not strip Black women of their agency. Whether I was reading historical romance or any of the books mentioned above, there was [always] an underlying respect of Black women, our identities and our experiences [in the text I consumed]. That is why to me, the way [for Black women to reclaim] their agency would be to look into themselves and their histories. We tend to assume that Black women of the past were prudes who shunned pleasure and desire but that wasn’t always the case. For some women, learning that our ancestors embraced their sexual selves may be key in understanding that it’s okay for them to follow suit. I’m also a fan of taking time and space to connect with oneself through meditation or even therapy as a means of reclaiming what is lost or hidden.

“For some women, learning that our ancestors embraced their sexual selves may be key in understanding that it’s okay for them to follow suit.”

What do you hope your audience takes away from the stories in She Called Me Woman?

Editing She Called Me Woman was important to me because I believe in the importance of telling stories. Even if some people don’t want to hear these stories, they should still be out there. While working on She Called Me Woman, I was thinking about the future [of Nigeria]. I would read academic essays arguing that there was no homosexuality in Nigeria because local languages apparently have no name for it. I found it was largely accepted that same-sex relationships ‘arrived’ with Arab and European colonialism, and this didn’t sit well with me. To me, these Nigerian academics could only claim that homosexuality never existed here because people who engaged in same-sex relations in the past didn’t talk about it and because it was not documented. I would imagine future generations arguing the same thing about the Nigeria I know. Many Nigerians are virulently homophobic and so She Called Me Woman is there to remind that LGBTQ+ Nigerian women are here, have been here and will always be here.

Read more on African women’s sexuality in the Roundtable discussion featured in Issue 4, The Reverie Issue.

Purchase a copy of She Called Me Woman: Nigeria’s Queer Women Speak here.

See more of Rafeeat’s work here.