Image: We Wear The Mask I, Krista Franklin, 2014

artists in conversation Hamed Maiye and Krista Franklin discuss surrealism through a Black lens

words Elvira Vedelago

In light of the new photographic exhibition ‘An Ode to Afrosurrealism’ at the Horniman Museum & Gardens in the UK, African American poet and visual artist Krista Franklin and London-based interdisciplinary artist Hamed Maiye examine surrealism through a Black lens.

KRISTA FRANKLIN: Let’s talk about surrealism. I want to approach it from a different vantage point because I feel like we spend a lot of our time trying to define what surrealism is and I don’t feel like that’s functional. I’m more interested in what your earliest memory of the surreal is?

HAMED MAIYE: Probably dreams - the moment I realised there is a break in reality.

KF: I grew up in a Pentecostal church. There was a lot of charged, spiritual energy around me as a child. So I grew up with this concept that there was no difference between the seen and the unseen. They exist at the same time and it’s just about how you navigate that space. That’s probably my earliest encounter with the surreal. I feel like as Black makers right now - I’m not going to say that it’s a trend because I feel like Afro-futurism is more of a trend right now - Afro-surrealism is building up a kind of momentum as a concept. I have mixed feelings about that.

HM: I don’t want to say I have a problem with Afro-futurism but I think it’s quite a flattening artistic ideology. I’ve been really obsessed with Afro-surrealism in the past couple of years because I feel like a lot more falls under that term. Especially the emphasis on now. With Afro-futurism, the premise of it was always speculative futures. For me, as someone who very much lives in now and needs to investigate my immediate context, Afro-surrealism has always felt more relevant.

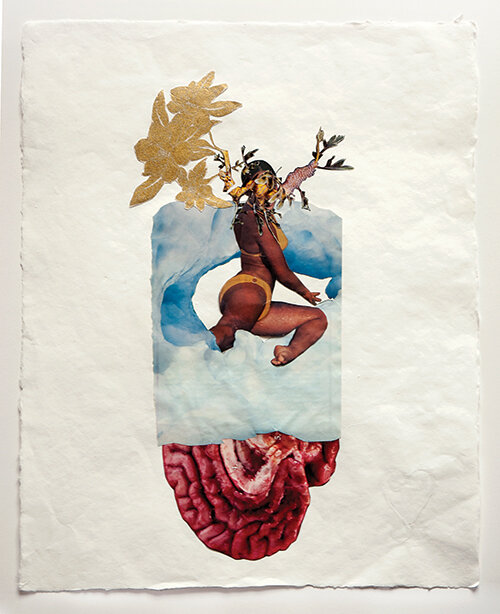

The Exhorter, Hamed Maiye

KF: In your work, where do you see it showing up?

HM: It comes from the final visualisation. But also, as you said, the seen and unseen, the visible and the invisible.

KF: Do you play around with mysticism in your work?

HM: I don’t think mysticism is something that I’ve really explored. I’m quite interested in iconography and symbolism.

KF: Looking at [how some of your work features] the crescent moon and the star, I [see] that as a mystical symbol. It’s an iconographic Black symbol. It’s something that we identify with as Black, even if you don’t quite know what it means. For me, I play a lot with symbols like that - they show up in my work in different kinds of forms. I also think about material as a mystical device. Like [with] chalk, you can write a symbol on something and protect it.

HM: For me, with material, there comes a tangibility. It can help open portals, it can help define things.

KF: To me, it’s ritual. I think when people talk about my work in the context of the Afro-surreal, or when I refer to my work in the context of the Afro-surreal, it doesn’t always show up in a very literal translation. Sometimes it’s embedded or hidden. It shows up more, I would say, in my writing. Because [in] my writing, I tend to activate surrealist games like chance operations. [With my artwork] it’s more about the dynamic nature of Black expression, which is surreal in and of itself. It’s surreal to be a Black person where people don’t want to accept that you’re a citizen of the world and they try and deny that your experience is even real. There’s one question I wanted to ask you - because you said that you get more excited about the surreal - what excites you about the surreal?

HM: I get quite excited to see other artists’ imagination spaces. There’s something affirming about it. There’s an element of escapism in there, like reading into someone else’s work and trying to project into their landscape or their world.

World Peace at Your Fingertips, Krista Franklin, 2008

KF: I’m excited about the history of surrealism and the intersections of Blackness inside of that domain. Just tracking how Black folks before us become involved with it as a concept. What was it that made them interested in it in 1945? I did also want to talk a little bit about the commodification of the surreal. Because I feel like the surreal has always been about the outliers. It’s always been about the revolutionaries who overthrow governments. I think there is a [misguided] idea of the surreal as being dreamy and with flowers. I’m curious, why do Black folks right now choose flowers as this symbol? Why are flowers surreal? I’m annoyed as well as intrigued by it.

HM: I completely agree. I feel like flowers were brought in as a way to humanise our existence and almost justify an empathy towards us. It really became a trend. I appreciate flowers being in pieces. But flowers being the focal point, there is something quite reductive about it.

KF: I started thinking a lot more critically about it when I went to Martinique on a research trip and that’s the first thing that I actually saw, the abundance of the tropics. And it was enchanting as fuck! And that’s the first time I had seen bougainvillea too. I had read about it in books [and] Black literature, particularly out of the Caribbean. So that to me was very transformative. I did somewhat understand it as a symbol of the Afro-surreal in that it’s a nod to that tropical abundance that is associated with Blackness, in a poetic kind of way. And I use flowers in my work too but I’m very intrigued why it’s associated with the Afro-surreal. When I was in Martinique, that was the first time I had ever seen plants colonise something. Like a car on the side on the road and flowers literally taking over it. That was interesting and scary [laughs].

HM: What’s quite interesting is living in metropolitan environments and going somewhere that’s more natural, how that alone can be considered a surreal experience. It’s so far from your everyday reality.

A Call Back Home, Hamed Maiye

KF: I completely agree. I had been teaching this class for a while with my friend Ayanah Moor - who is a brilliant artist as well - called ‘Black in the Woods’. We’re looking at evidence of African diasporic images of Black folks in the woods. Because most of the time, [when] we think about Black people in the woods, we think about lynching. So how do we get away from [that] or [what] other images [exist] of Black people in the woods? All of that is in alignment with some of the preoccupations that I’ve been having around these visual representations of nature in Black art.

HM: I think sometimes for people to get into that space of imagining ourselves in those spaces, we have to pass it through [a European] lens. So as a reference, Alice in Wonderland. Does that make sense?

KF: It does but it makes me sad. So what are the other entry points that are directly connected to [the] African diasporic experience? For me, I think about Amos Tutuola[’s book] My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. And Marlon James’ novel that recently came out, Black Leopard, Red Wolf. I haven’t finished that yet but I was so angry with him for a while because - and I know why he did it, I understand the impulse - when he was getting ready to put it out, he said it was the ‘Black Game of Thrones’. And I was like, is it? [laughs] It’s brilliant but [it’s] closer to Tutuola’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts than it is to Game of Thrones. So I’m like, why can't you just say this some African shit?

HM: I remember going to a film conference last year and the subject of sci-fi came up. Within this, they really picked apart the context of sci-fi, so like aliens come and abduct you, they experiment on you, etc… And some people argue that sci-fi is based more specifically on the African-American experience. Being abducted, being taken to another land, being experimented on. I think that’s probably why writers like Octavia Butler are so important.

KF: Absolutely.

*This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Continue reading Krista and Hamed’s conversation in Issue 4, The Reverie Issue.