Image: Ines Longevial

Considering the correspondence between the female and mixed-race position in society, this personal essay explores the expectations placed on mixed-raced identity; questioning how we exist as women of the in-between?

words Lucy Lim

My grandmother said; ‘Lucy doesn’t like being English’.

‘We’re all horrible, aren’t we?’ my mum joined in, ‘we just do everything wrong’.

Their tone was teasing but to me the air felt thick with spite and the strong feeling that in some way, I’d picked the wrong side. I might as well have declared that I was now a Tottenham Hotspur fan.

‘She wants to be Chinese,’ my grandmother continued, ‘we’re not good enough’.

‘She could be a lawyer the way she argues’ my mum said, in some kind of agreement.

‘A little firebrand.’

My cheeks were hot and prickly, and I took my cue to leave, clearing away the teacups. My brother sat silently across from me, pondering the crossword.

*

Racialised identities govern our notions of culturally intelligible humans. It seems we are all now native speakers of the language of ‘performativity’ and ‘discursive subjectivity’ and there is therefore an established circle of thinking that speaks confidently about the ways in which categories of identity are governed by regulatory practices and the expectations that others impose upon us.

The mixed-race person struggles in that space because conformity to a kind of stable ethnic classification is not immediately available. Even taking up a position is fraught if that position turns out to be the ‘wrong’ one required for acceptance in a particular society. Embarking on a path of selective ethnic identification entails an obligation to others that the mixed-race person is able to justify the side they pick and is able to adequately validate their performance.

We owe to others, therefore, a certain amount of energy in substantiating the identity we arrive at. There is a correspondence between the female and mixed-race position in society, in that identity is often conferred upon us through the act of being observed. Does my performance look right? What does it need to look like for me to survive in this social order compared to another?

As the youngest woman in my family, I have an acute sense of what it means to be ‘good’; a sense of obligation to my family to provide a level of care and compassion that is proportionate to the emotional labour denied by my male relatives. Asserting mixedness in this context is itself a disruptive force, an act of self-identification which does not conform to the demand for female altruism and humility. The endeavour to try and root myself across boundaries upsets the concept of family as the basis for a sense of belonging. To deliver against expectations of instant familial affinity and understanding means foregoing an attempt to define as in-between.

*

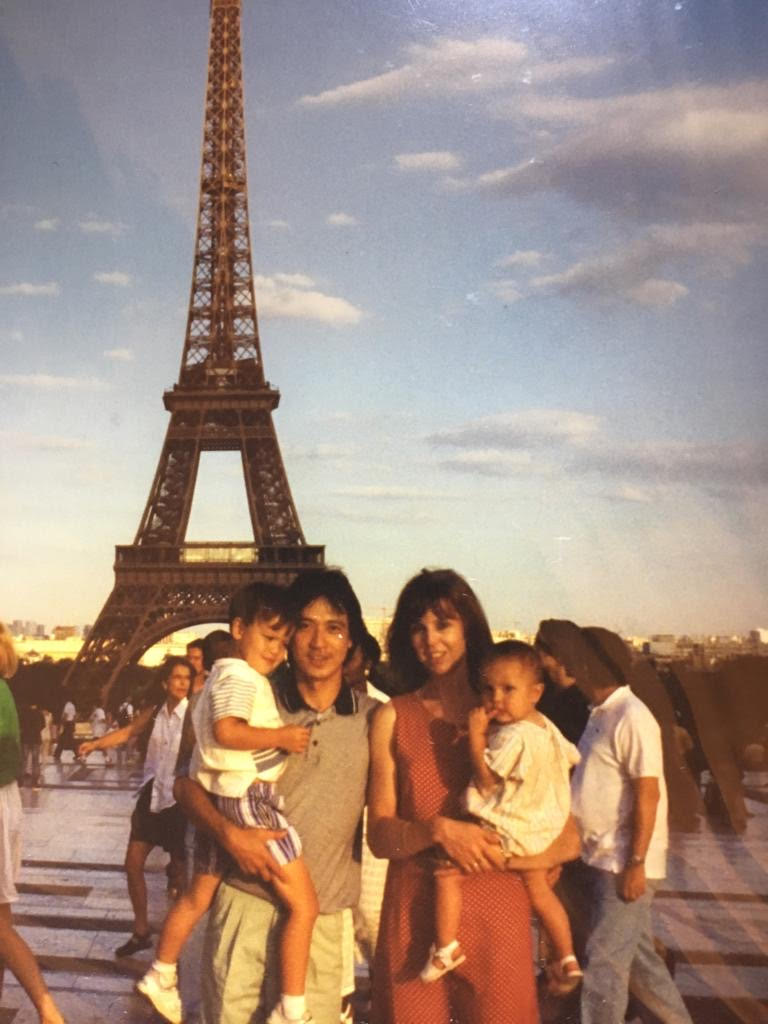

It is late on the car ride home and we are both tired. The glare of the motorway lights on the windows punctuates our increasingly heated discussion, tracking the staccato of our voices. We are somehow talking about Hong Kong and the Chinese Communist Party and propaganda. I sense that I am on the right side of history in this debate but the wrong side of ethnicity. ‘You are not culturally Chinese,’ says my dad. ‘You have gone backwards since going to university’ (‘Backwards’ def. ‘assertive’) – universities I broke my back to be admitted to and to succeed at to make him proud. ‘You are not right to talk to me like that, you must respect what I say.’ And finally, ‘Chinese people are superior.’ So, what does that make me?

*

If one ‘side’ is owed familial loyalty, the corollary is a sense of dissonance from the other. To minimise the threat posed by the ways in which I might explore my mixed-race identity, I am bound to marginalise the ‘foreign’ culture, the part which produces difference in the default, the disruptor.

In Stoppard’s Arcadia, the precocious teenager Thomasina describes to her tutor the Second Law of Thermodynamics – the gradual decline into disorder or randomness – heat is always lost, energy is dissipated, entropy takes over. ‘When you stir your rice pudding, Septimus, the spoonful of jam spreads itself round making red trails like the picture of a meteor in my astronomical atlas. But if you stir backward, the jam will not come together again’.

So, it is to be mixed, or specifically, to be mixed-white – ‘disorder into disorder until pink is complete’ – with no memory of what the separate inflection looked like before. ‘Indeed, the pudding does not notice and continues to turn pink just as before’.

In her exploration of the situational selection of identity amongst ‘Malays’, Nagata (1974) suggests that the three main considerations made by individuals when selecting ethnic identities are ‘the desire to express social distance or solidarity’, ‘expediency, or the immediate advantages to be gained by a particular reference group selection on a particular occasion’ and the ‘consideration of social status and upward or downward social mobility’. Yet these choices are not free and equal. Just as the jam is subsumed into the pudding, the mixed-race person is forced to conform in ways they may not have independently chosen, unable to disaggregate the component parts and deferring to the dominant ethnic categorisation of those around her.

Female mixed-race bodies face a double bind; too much and too little gender, too much and too little ethnicity, very little of any true ‘self’.

For that reason, one part is always lost, and it is quite easy to be both too much and too little. This experience is not unfamiliar to women whose bodies are routinely inscribed with gendered identities that are not of their own making. It is the same reason that female bodies cannot be simultaneously demure and obedient while sexually attractive and satisfying. Female mixed-race bodies face a double bind; too much and too little gender, too much and too little ethnicity, very little of any true ‘self’.

*

Our second-year house had a large basement kitchen. It was dark and low ceilinged, bathed in stark yellow light to illuminate our late-night discussions of undergraduates setting the world to rights. In the depths of one of these ‘academic’ debates one night, my best friend and then boyfriend told me that I couldn’t call myself ‘Asian’. I was ‘such a white girl.’ Give us examples, they demanded, of the things that made me otherwise. In my embarrassment, I cycled through a list of East Asian stereotypes that I conformed to, to offer up as evidence of some essential identity that I could call my own. More so than usual, it felt like a deep sense of failure that I could not speak my father’s language or had not lived in his country. I never asked the questions thick on my tongue: what would it be to be ‘such a mixed-race girl’, what counted as Asian? I knew I’d transgressed some unspoken line and I had no proof, no blood quantum, to refute the accusations.

*

This is the reason I apologise in mixed-race spaces. This is the reason I say I’m passing. This is why it feels like I’m outing myself as an ethnic minority when I’m asked where I’m from or what I am. I sat on this conversation for five years, ruminating on who had been right and wrong, reluctant to raise my questions for fear of accusing my friend and ex-boyfriend and causing them some discomfort over an event that I was sure neither of them would remember. They are men I love and respect greatly and the feeling lingered that to reopen the conversation would be to in some way tarnish the gratitude I had for them.

In the course of writing this piece and contemplating selfishness, I chose to broach the subject, to experiment with doing the selfish thing. My friend has been warm and receptive, and I am loathed to keep him ‘on the hook’ for things he said as a 19-year-old as we still played at being intellectual grown-ups. My ex-boyfriend has told me that he cannot engage with me on the subject as an ex-girlfriend and I have been left with a bitter taste in my mouth. True, we tread awkwardly the line of being friends and the breakup was messy and difficult as many breakups are. I cannot hold him to account for the feelings he may still have yet to process or the boundaries that he feels need setting. But it is deeply upsetting to me that after five years of waiting, the answer to what it means to be selfish as a mixed-race woman is for that selfishness to be denied.

For women of mixed heritage, the claim to particular identities and the question of what constitutes a ‘legitimate’ identity is frequently decided by others. At the same time that we exemplify the complexity of defining a race-based culture based on one factor, we are policed by others according to that chosen factor. In a bid to resist the self-effacing stance I have taken to my race following this incident, I have taken to cultivating a vocal interest in Malaysian food. It does not go unnoticed to me that in doing so, I am indulging in the same stereotypes demanded of me in that conversation, that I am reifying a monolithic race culture to legitimise my own claims to mixed-race identity.

How do we exist now as women of the in-between? How can we claim ourselves when others deny the possibility? How do we wear this culture, eat this culture, act this culture without exercising this labour for the comfort of those around us? Each of these questions unfolds, with no clear resolution or direction. The best we can do is muddle between the boundaries and seek to better understand how to wield ambiguity rather than be victims to it.

Read more from Lucy in the Mixed Identity Roundtable featured in POSTSCRIPT’s Issue 2.